Types and usage

Features of the Latin script that continue to shape how we communicate in print go back to the century that followed the invention of movable type in Europe and even further to ancient Rome.

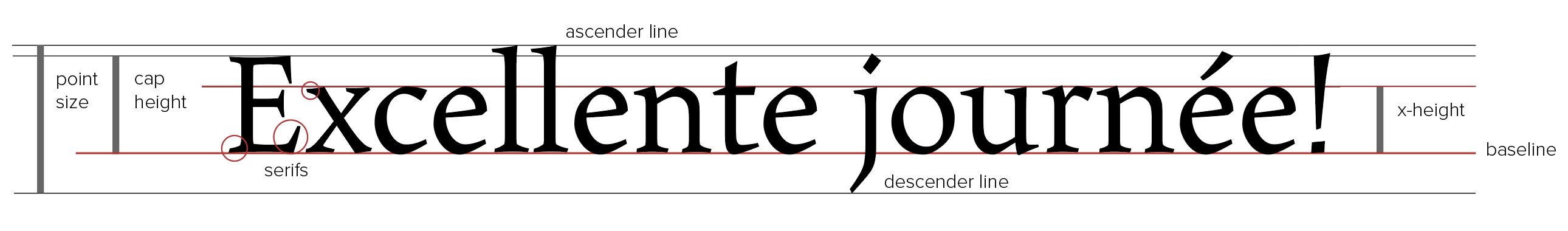

The profile of a font

One of these ancient features is the presence of serifs, or projections at the extremes of certain strokes, as in the upper case e and in x here.

Profile of a serif font (right click to view full size)

Each font has a number of distinctive elements, notably its x-height, or the height of lower-case characters, and its capital height. The full point size of a digital font is the distance between its descender and ascender lines (typography, needless to say, has its own distinctive terminology).

A font’s x-height has an important bearing on its legibility.

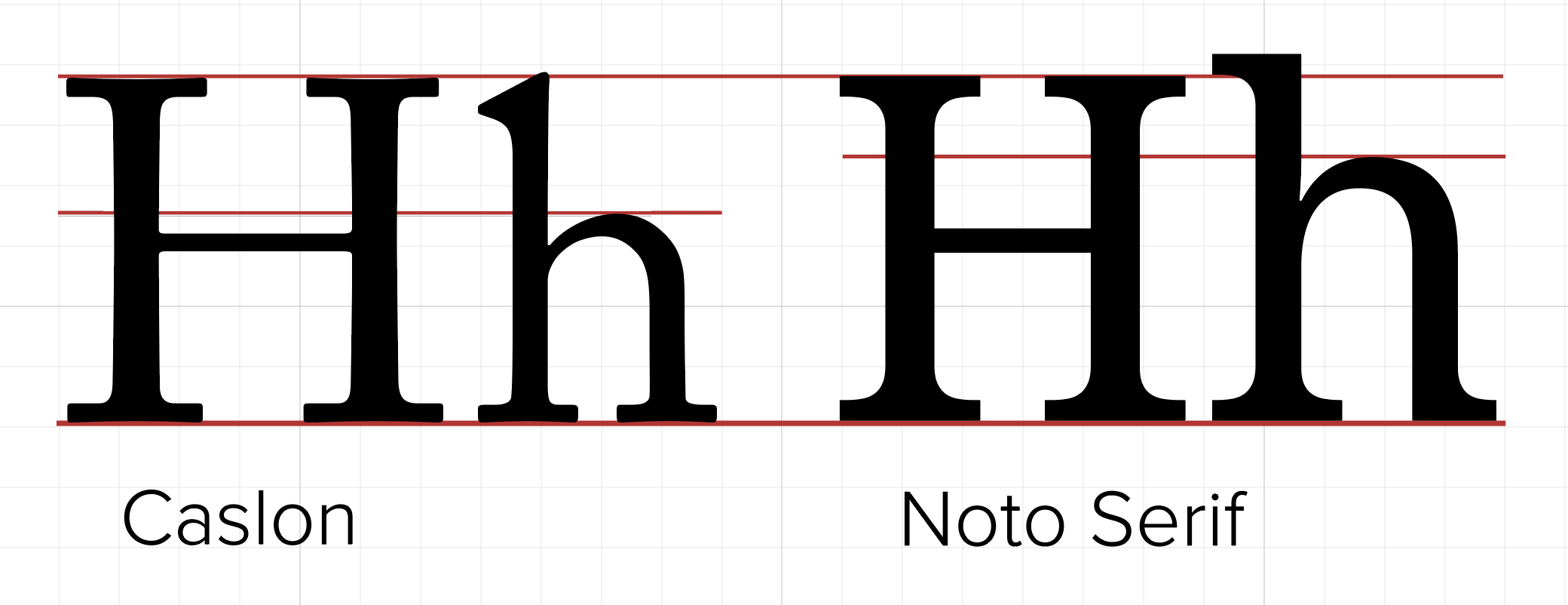

Contrasting x-heights

Fonts of quite similar point size can have x-heights that differ quite sharply. The raised x-height of Noto Serif means that it is more legible at smaller point sizes, provided that inter-line spacing is slightly increased.

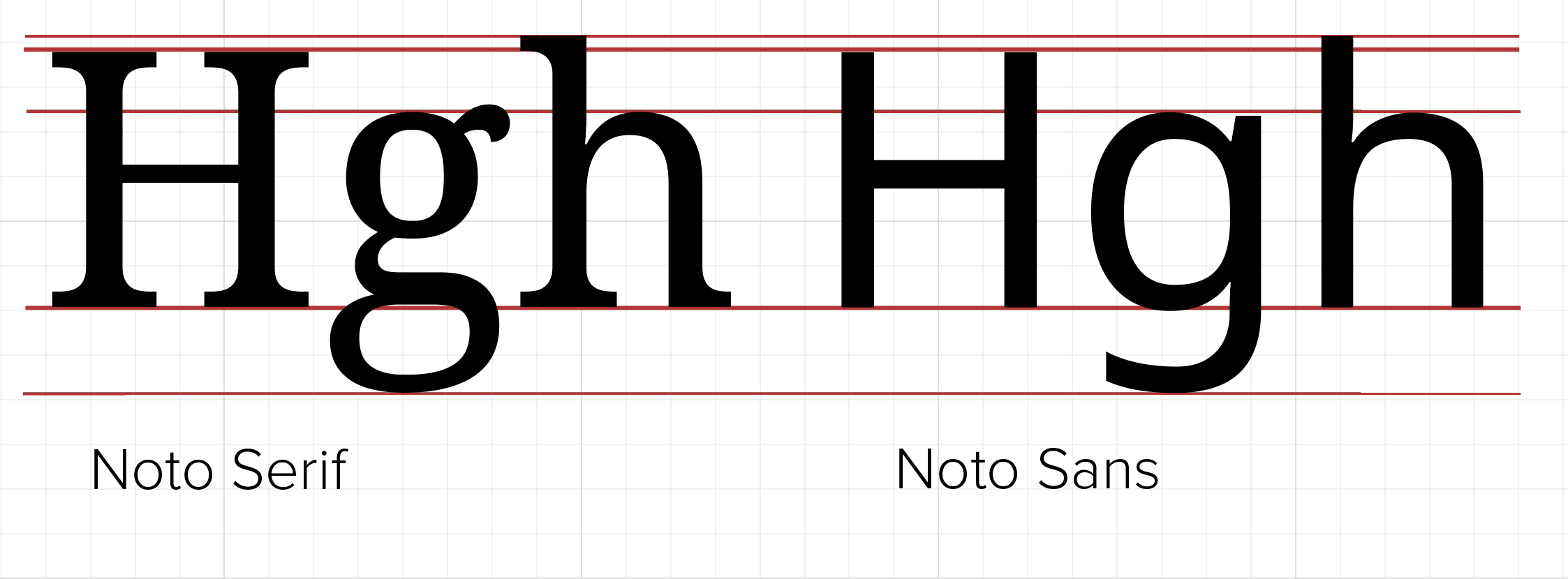

Serif and sans serif

Many features of the design of serif fonts derive from calligraphy. Sans serif fonts, by contrast, are more geometric and less ornamental in character.

Serif and sans serif

Even so, some sans serif fonts retain the contrast between thinner and thicker elements of a character: compare the shoulder of the letter h in the two forms of the Noto font, or the counter of the sans serif g. Note also that in the serif and sans serif forms of Noto the x-height, capital height, ascender and descender lines are identical. Today, many fonts exist in the form of font families encompassing serif and sans serif forms with many variants of style and weight. Noto Sans is the font used in this site.

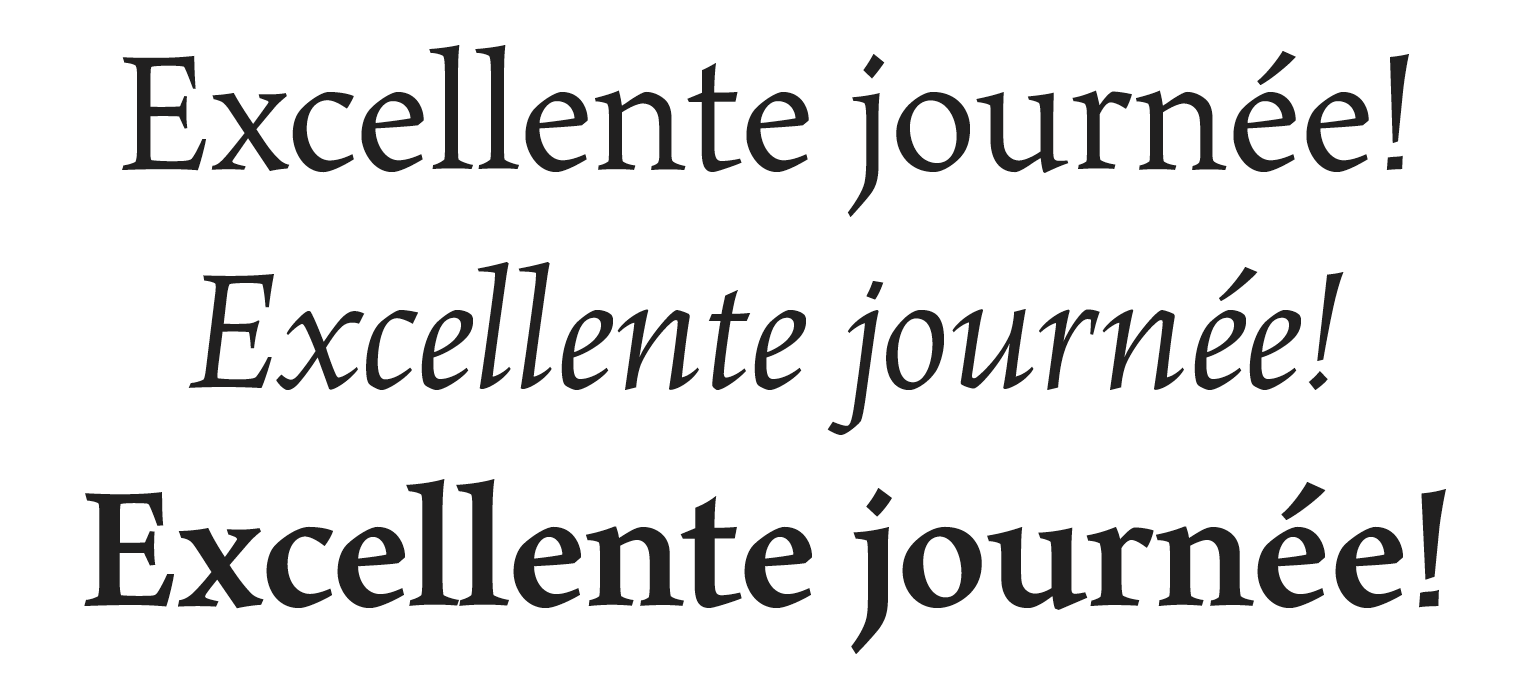

Styles and weights

Italic fonts were first used in the sixteenth century to print material in Latin.

Styles and weights: roman, italic and bold

Nowadays, they are used for more specialized purposes, e.g. to emphasize individual words (especially in serif fonts) and to denote the titles of books and other full-length works, e.g. Le città invisibili, Le Mariage de Figaro. Word-processors sometimes present block quotations by default in italics, but this is not a style that you should follow in your essays; likewise, italics should not be used for inline quotations.

Bold fonts can also be used for emphasis and also to highlight the structural hierarchy of elements of a document, e.g. in headings. Note that here all three typefaces have the same point size, but differ in width.

OpenType fonts

OpenType is the most widely available font format available today. This is a file format that allows several different font variants to be combined in a single file — extending to features that we will now consider, including small capitals, ligatures and various forms of numerals.

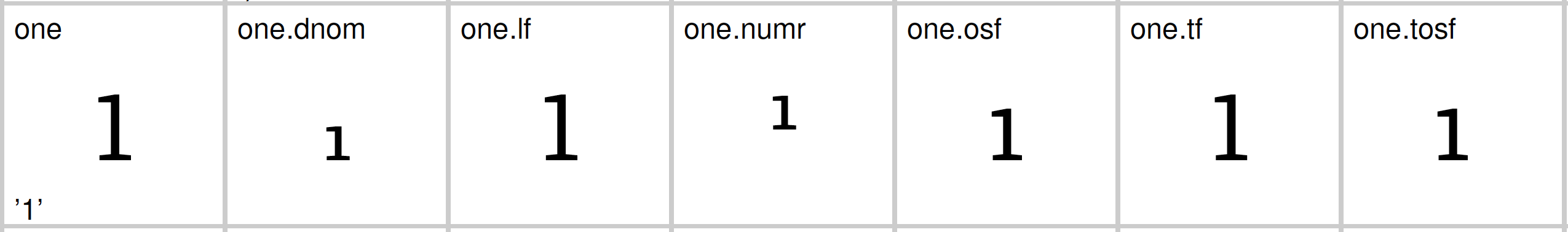

Variations on the number 1

Here are the several forms of the number 1 in the font Faustina, including forms used in fractions, lining and non-lining versions with tabular and proportional variations. It is possible to activate any OpenType forms you wish to use in a document using controls in a word-processor.

Small capitals and structural divisions

Small capitals, which are characters that take the form of capitals but are proportional in height and weight to lower-case characters, emerged also in the sixteenth-century, typically to designate headings or other structural elements.

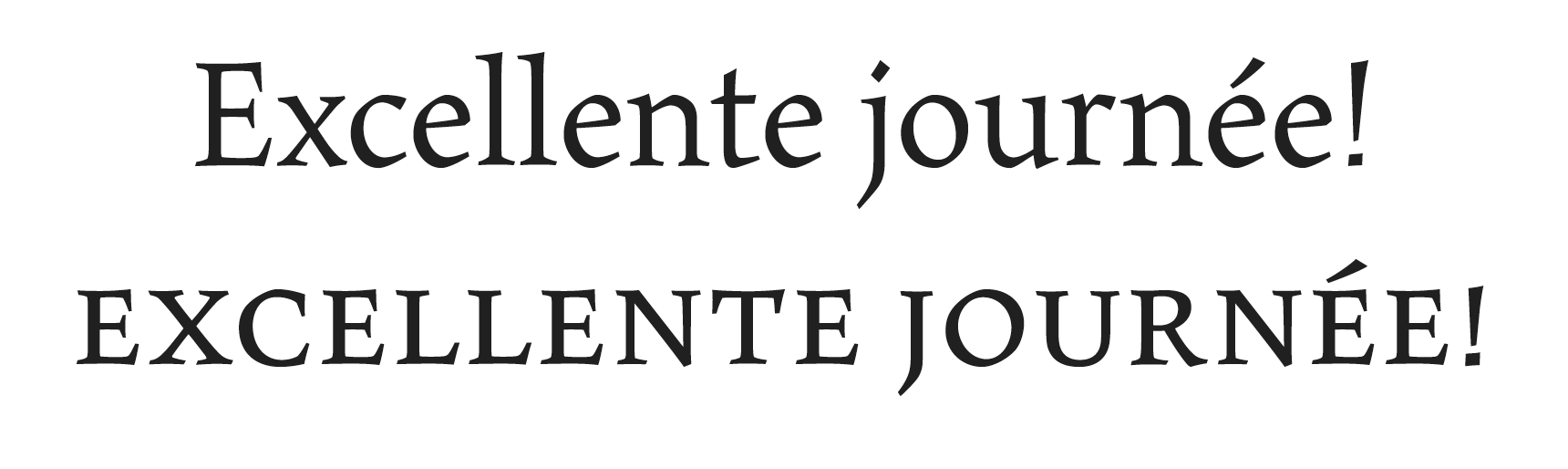

Small caps

As you can see here, they are marginally taller than the font’s x-height.

Roman and small caps

An unbroken series, as here, without any upper case characters is referred to as even small capitals and is a form often used in headings, and in page headers and footers. Note that this font also incorporates a form of the exclamation mark that is in proportion with the small capitals.

The legibility of small caps demands that what is termed the line’s tracking, in other words, the space between characters, is increased: hence the greater width of the second line.

Kerning

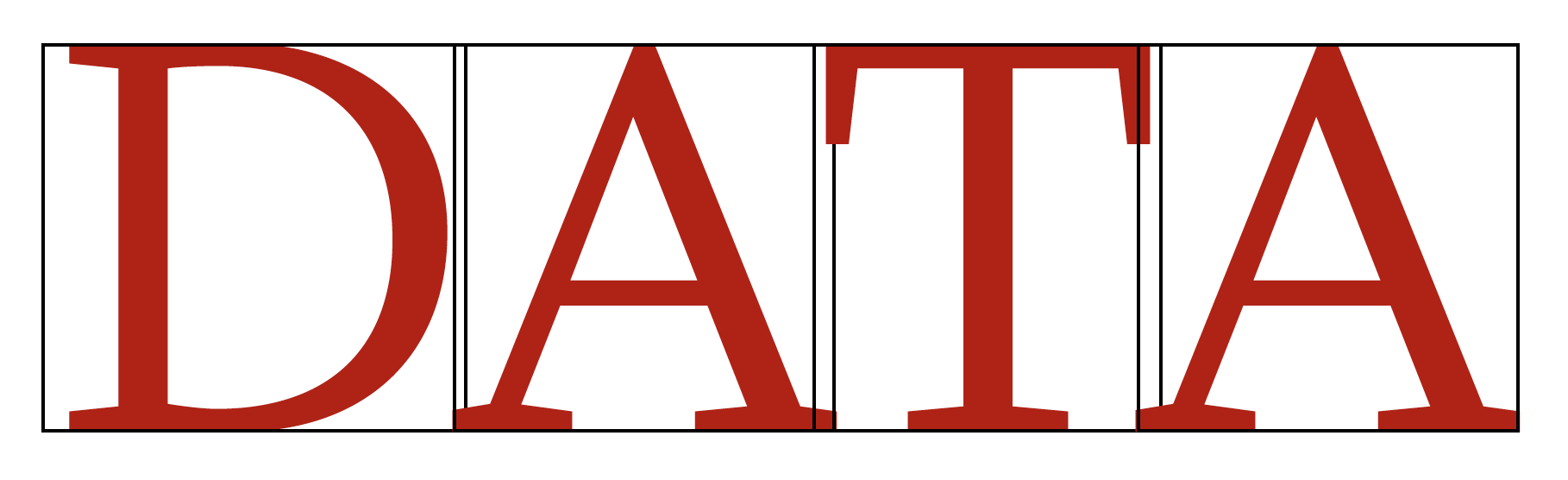

Even where the tracking in a given font may have been varied, some upper-case characters call for further adjustments. This form of adjustment is called kerning.

Top line: no kerning

You can see here that the spacing between the first three characters in the top line looks out of proportion with the rest.

Kerning applied

Here is the second of the two lines with each character enclosed within a bounding box. Kerning is a special form of adjustment between specific upper case characters in particular. As you can see, when kerning is applied the a and the v all notably overlap, making the string as a whole appear more evenly spaced.

Variable kerning

In some cases, several characters in a row will require kerning, though to different degrees according to the specific combinations that may arise.

Digraphs and ligatures

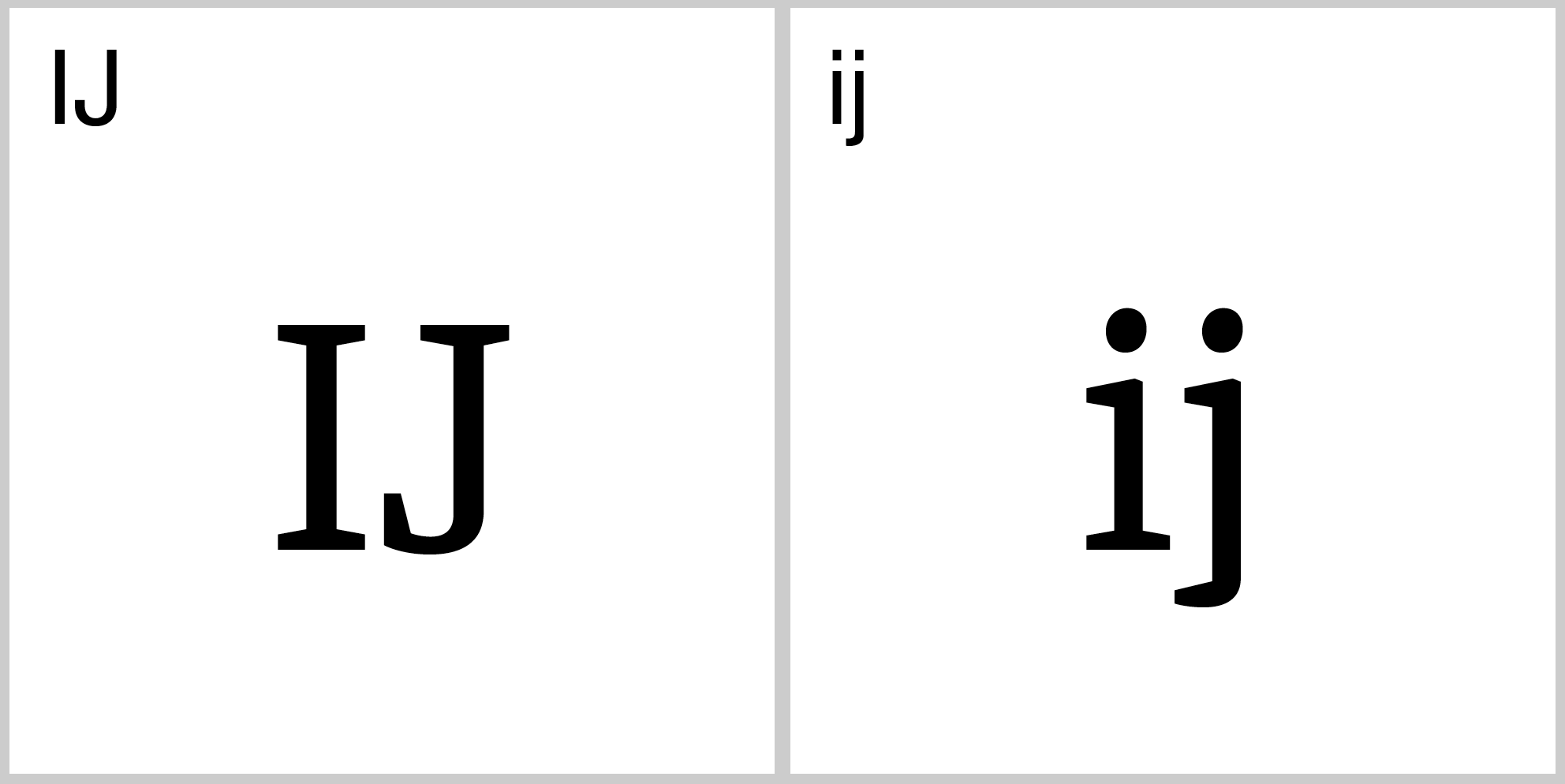

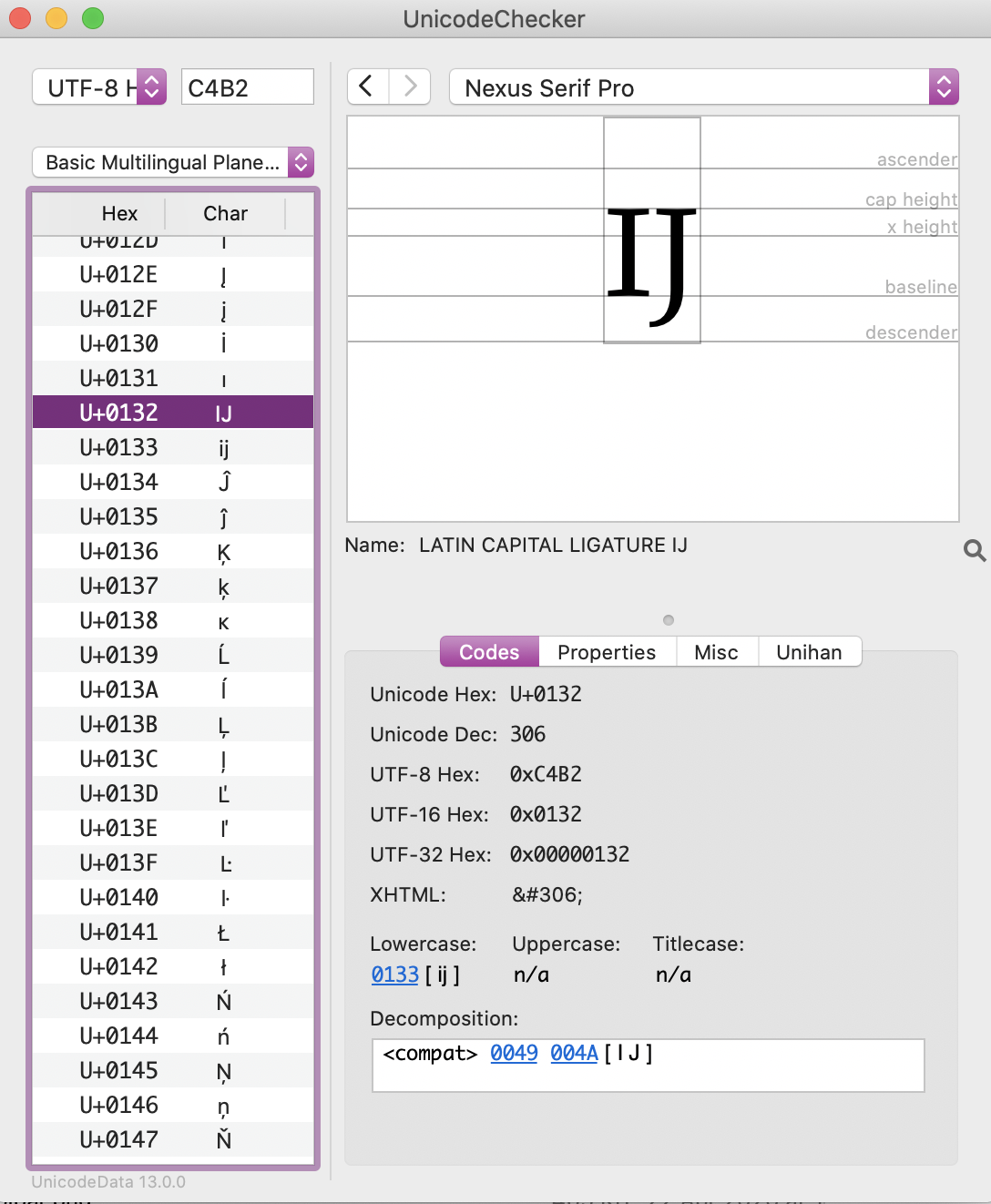

In some scripts, a single printed character can be composed of two components. This feature is termed a digraph: here is an example of a character that represents a discrete diphthong in Dutch and belongs to the Latin Extended-A block in Unicode.

IJ in Dutch: upper and lower case

In other words, this character is different from i and j printed side by side, which is why it has its own Unicode code point.

IJ: a composed character in Unicode

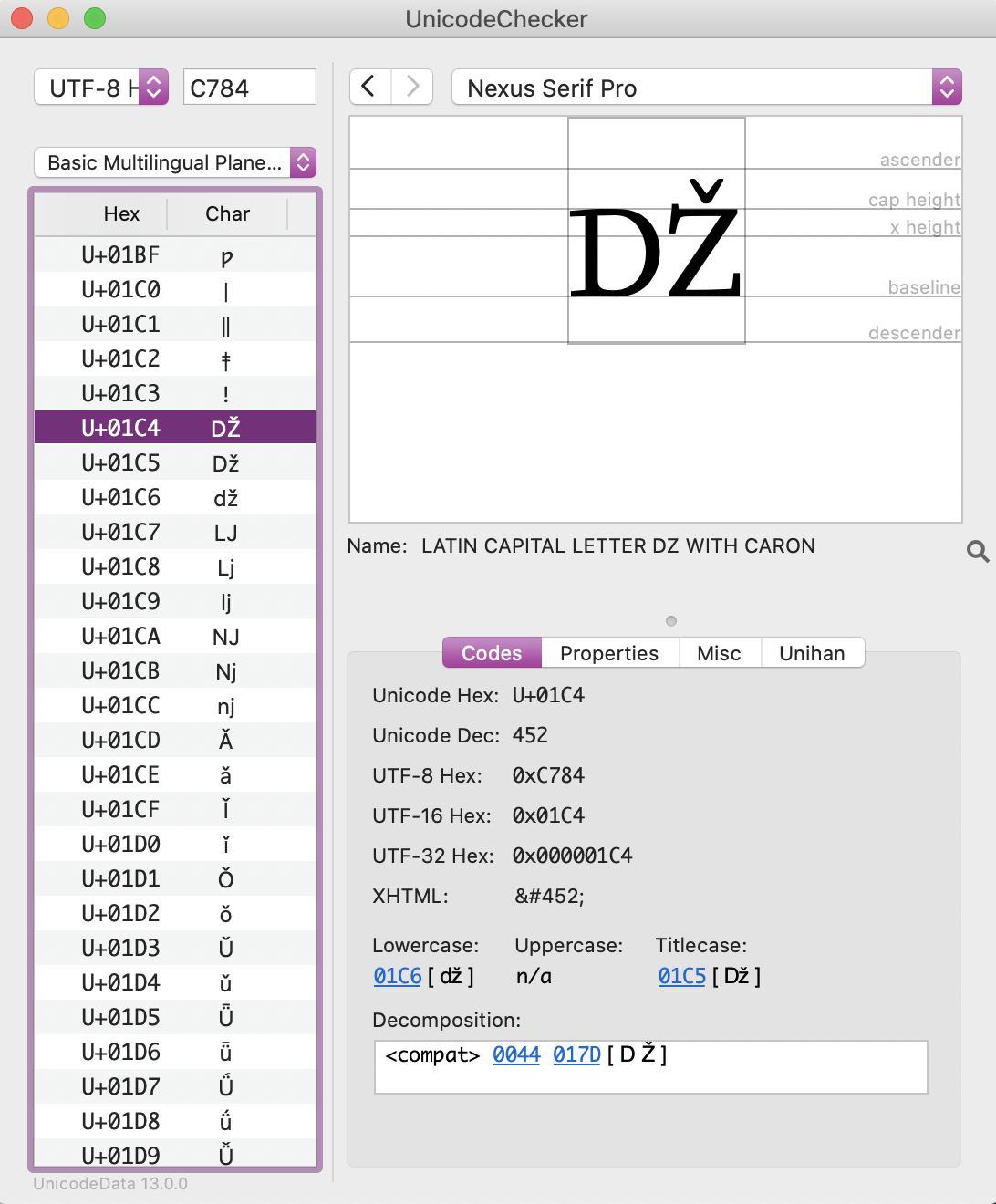

Another example is the character Dž and its lower-case equivalent dž, which are used in Croatian script. A further variant is the double capital form.

Latin capital DZ with caron

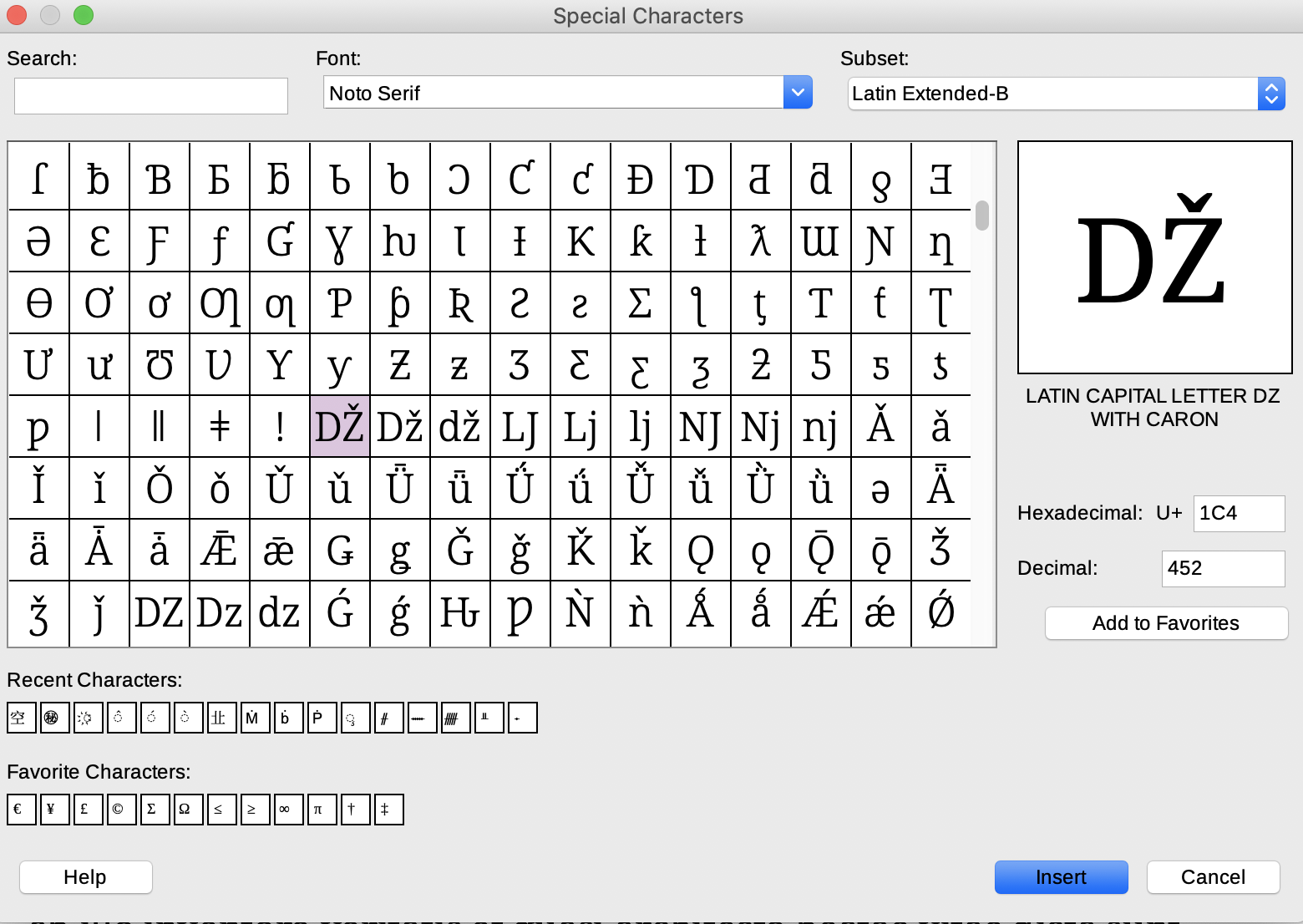

All of these three characters form part of the Latin Extended-B block.

Latin Extended-B in Unicode

See if you can identify them also in the Noto Serif character set.

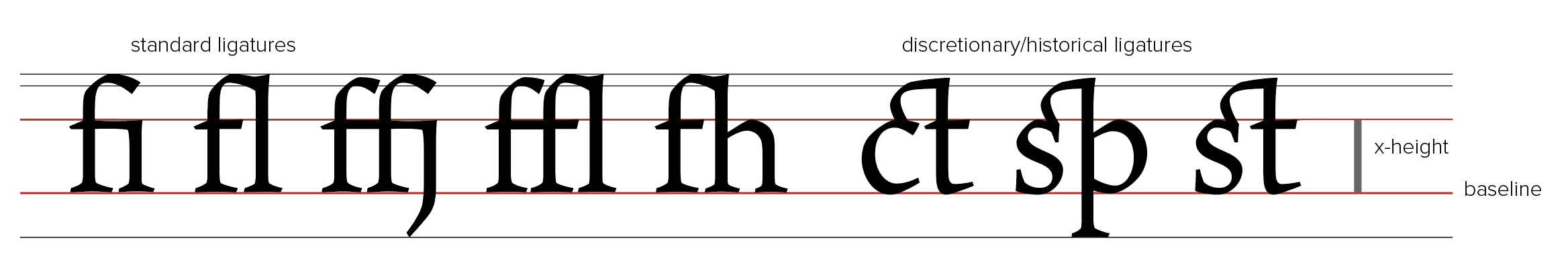

A ligature is another form of joined character, but with a different purpose.

Ligatures

Today, what are termed standard ligatures are joined characters that avert otherwise awkward clashes, e.g. when an i or l follows an f. It is a good idea to activate these ligatures if you notice that clashes do arise in the font that you may be using.

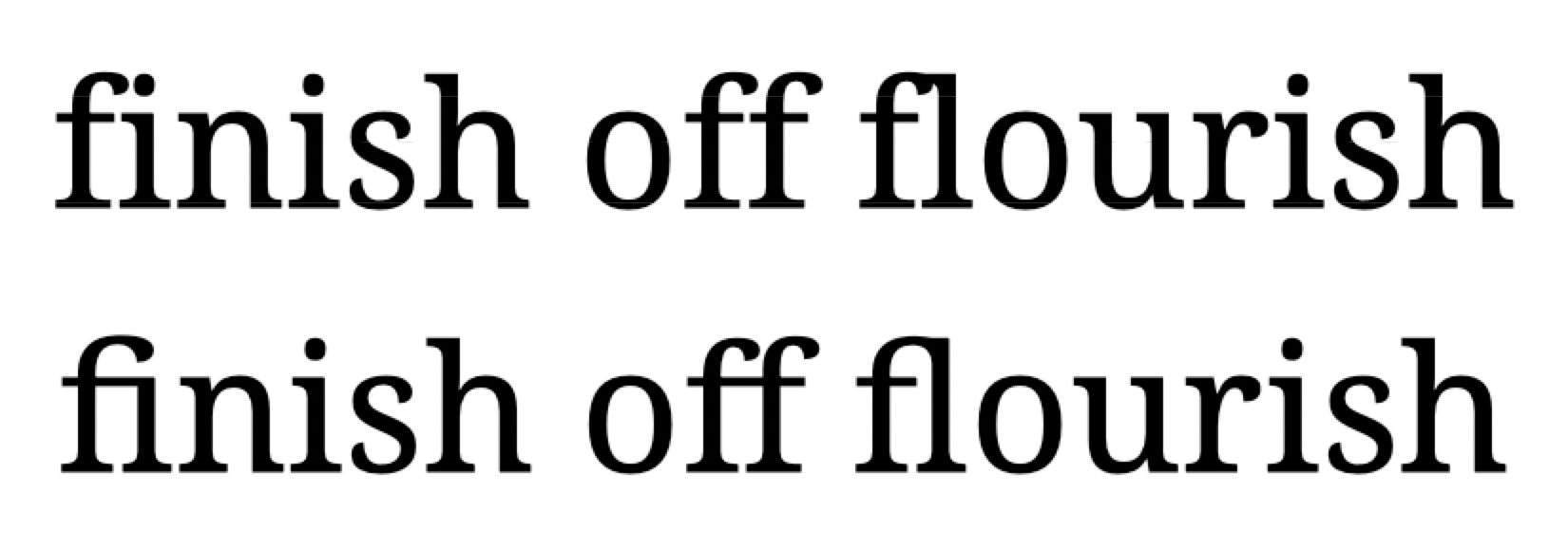

Noto Serif: with and without ligatures

In the case of Noto Serif, f and l are liable to clash, as you can see in the top line.

You can, however, opt for fonts which are designed in such a way as not to require ligatures, like Liberation Serif, which is the default open-source font in Libre Office.

Liberation Serif

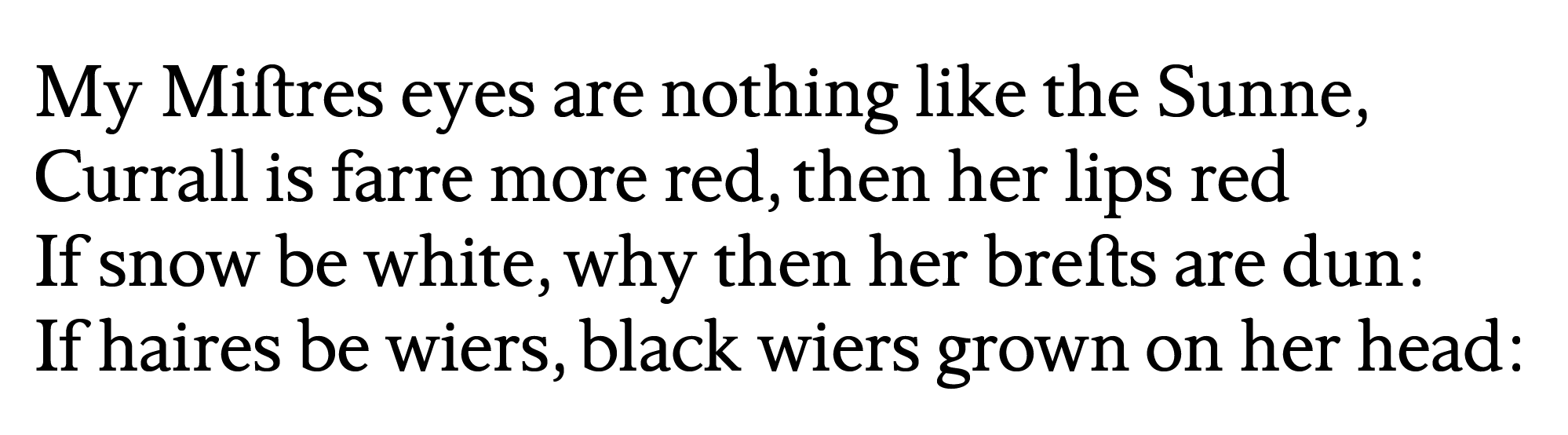

OpenType fonts also often include historical or discretionary ligatures, which are mainly ornamental or antiquarian. These should be avoided in your essays: for the reader of today, they are something of a distraction. On the other hand, if you are reproducing the typography of an original source, you may wish to make use of them.

Shakespeare, Sonnet 130: historical st ligature

Numerals

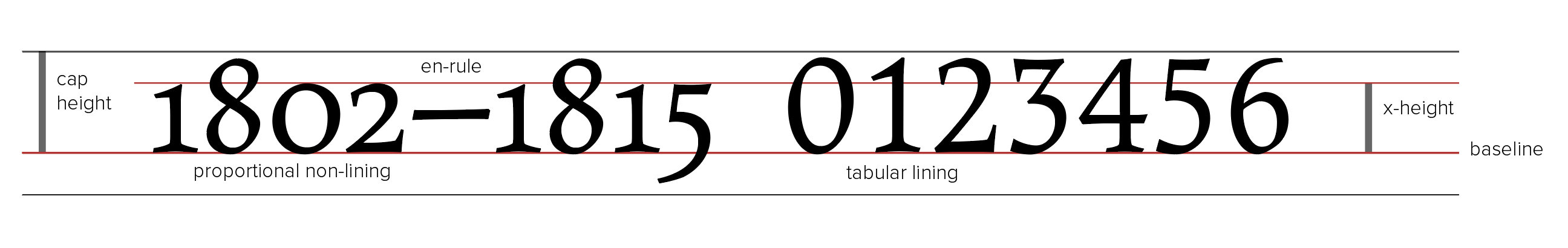

OpenType fonts typically include numerals in different styles:

- old-style (or non-lining) proportional numerals

- old-style tabular numerals

- lining proportional numerals

- lining tabular numerals

Varieties of numerals

Old-style numerals are appropriate to use in body text: they form an even line with alphabetical characters, so improving the legibility of your content. Tabular forms, whether lining or non-lining, are most useful in tables: columns of numbers then remain aligned from row to row. Lining numerals are as a rule slightly less than capital height. Where figures are to be combined with upper case characters, lining numerals are a better choice.

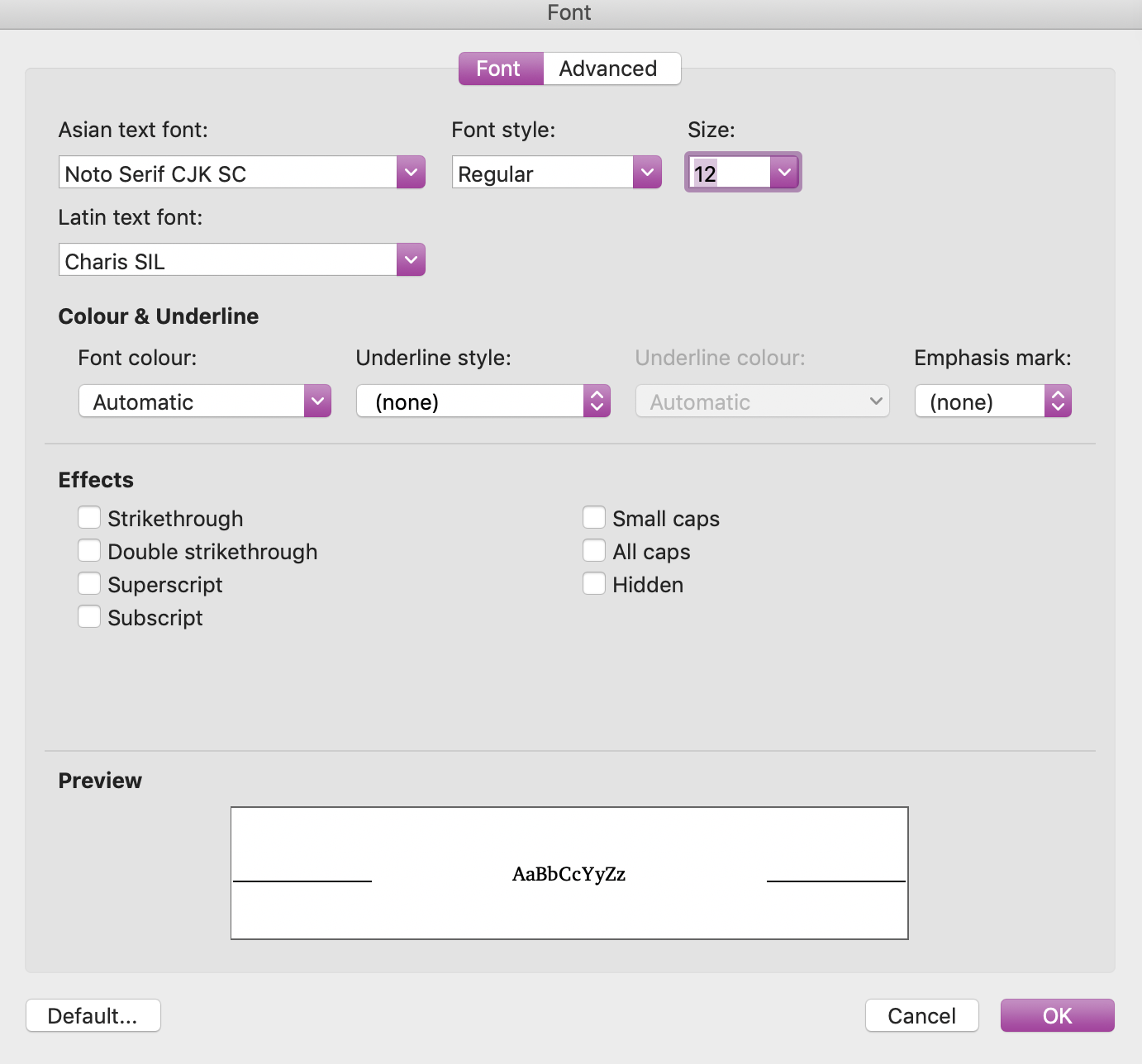

Accessing font features in word-processors

To access font controls in Word, select Format > Fonts, or use to keyboard to select CTRL+D (Windows) or CMD+D (macOS).

Fonts in Word

The basic controls are available in this interface. To access more specialized features, select Advanced.

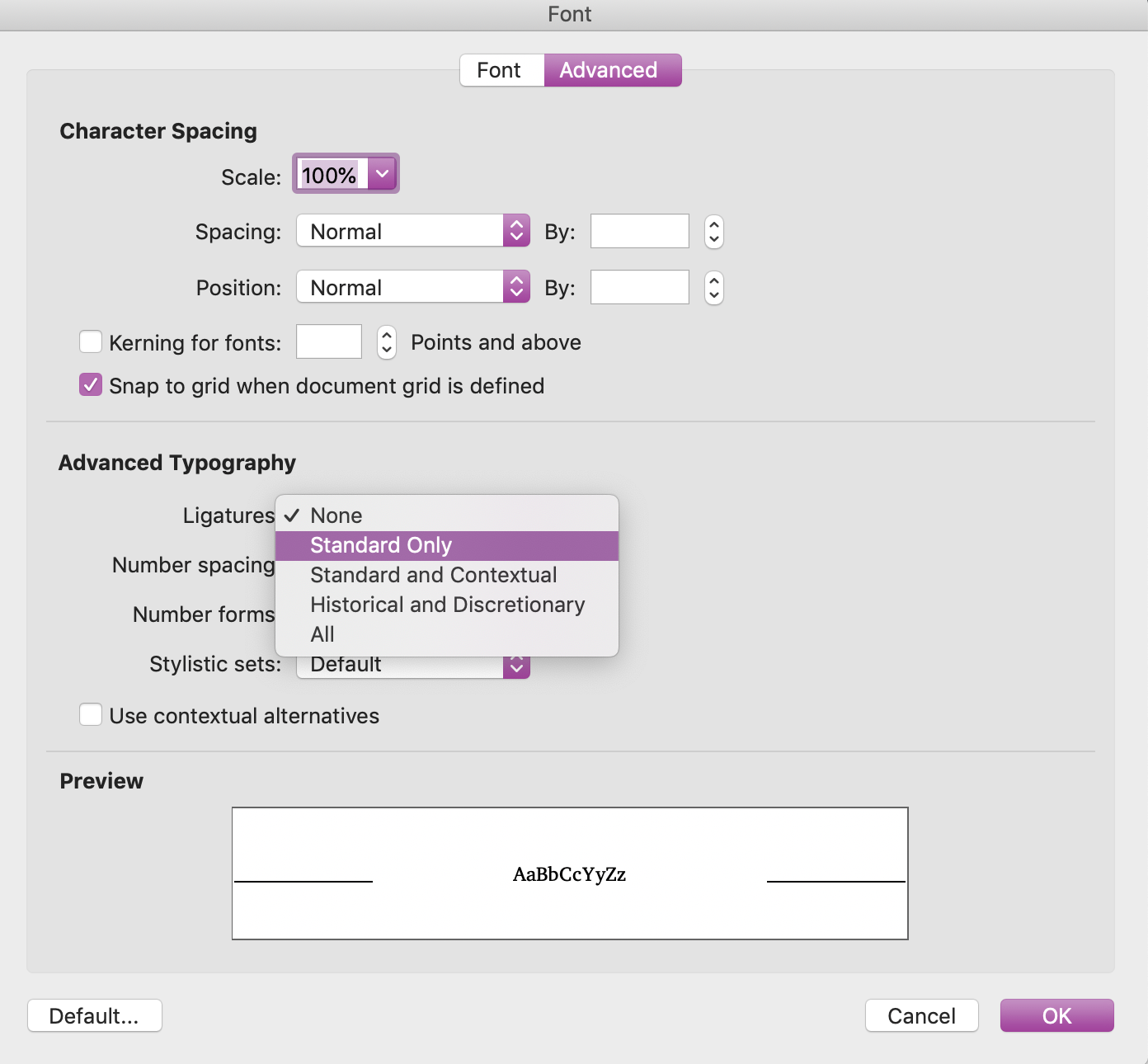

Advanced font options in Word

Here, you can control kerning, where necessary. You can also access OpenType font features, including ligatures.

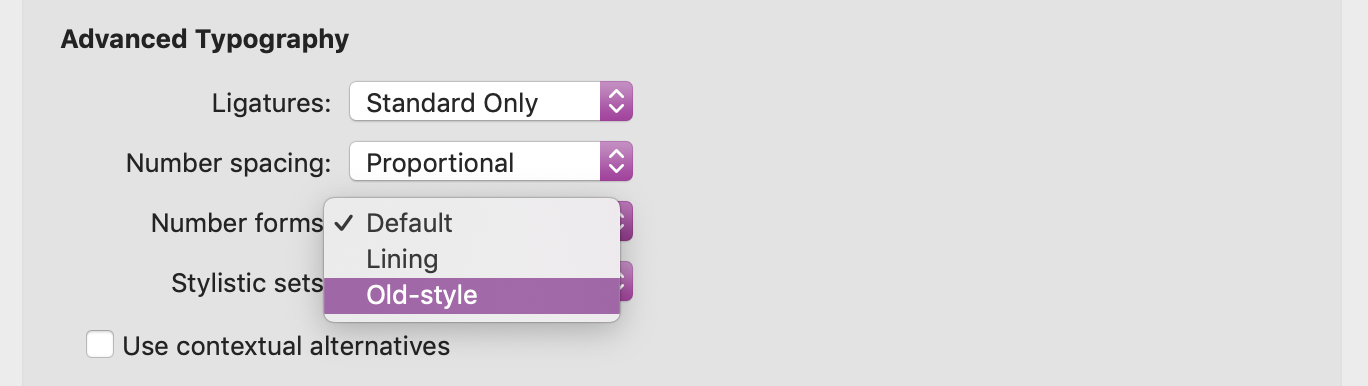

Numerals in Word

Here, proportional and non-lining or old-style numerals are selected.

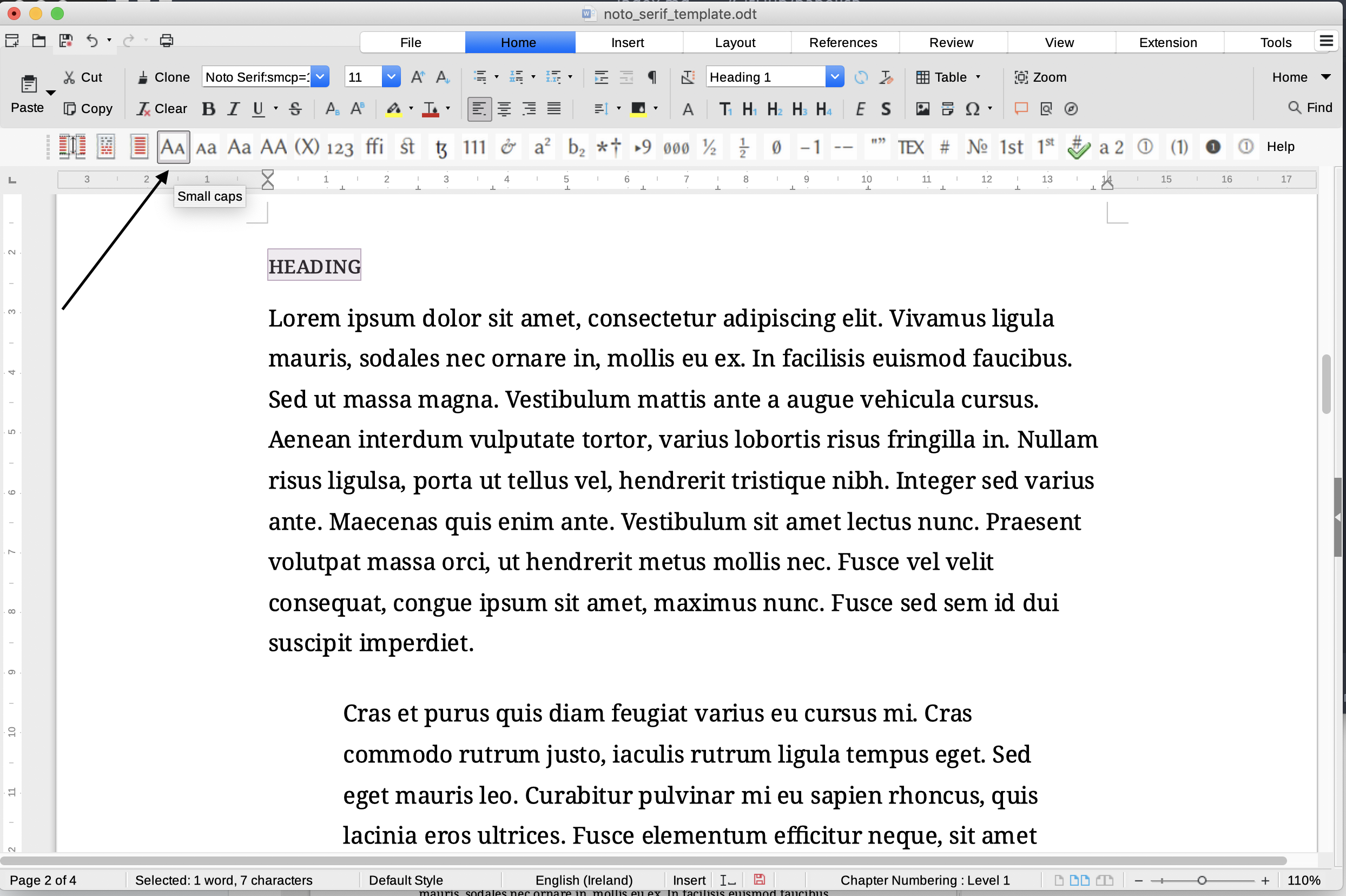

The best option to control font features in LibreOffice is to use the Typography Toolbar.

The Typography Toolbar in LibreOffice

Highlight a segment of text, or press CTRL+A or CMD+A to select all of the text in a document, and select the feature that you wish to apply.