What computers can do

At their simplest, computers are devices that can store or access data, on which you can perform a range of operations — for instance, a text file in which you can search for occurrences of a given word, a word-processing application in which you work on an essay, an academic source that you can read and annotate, an application or web service with which you can interact in the process of learning, or a dedicated search engine in which you can explore existing knowledge in subjects of interest to you.

These are all operations you can perform on a computer, but also, say, on a smartphone or a tablet.

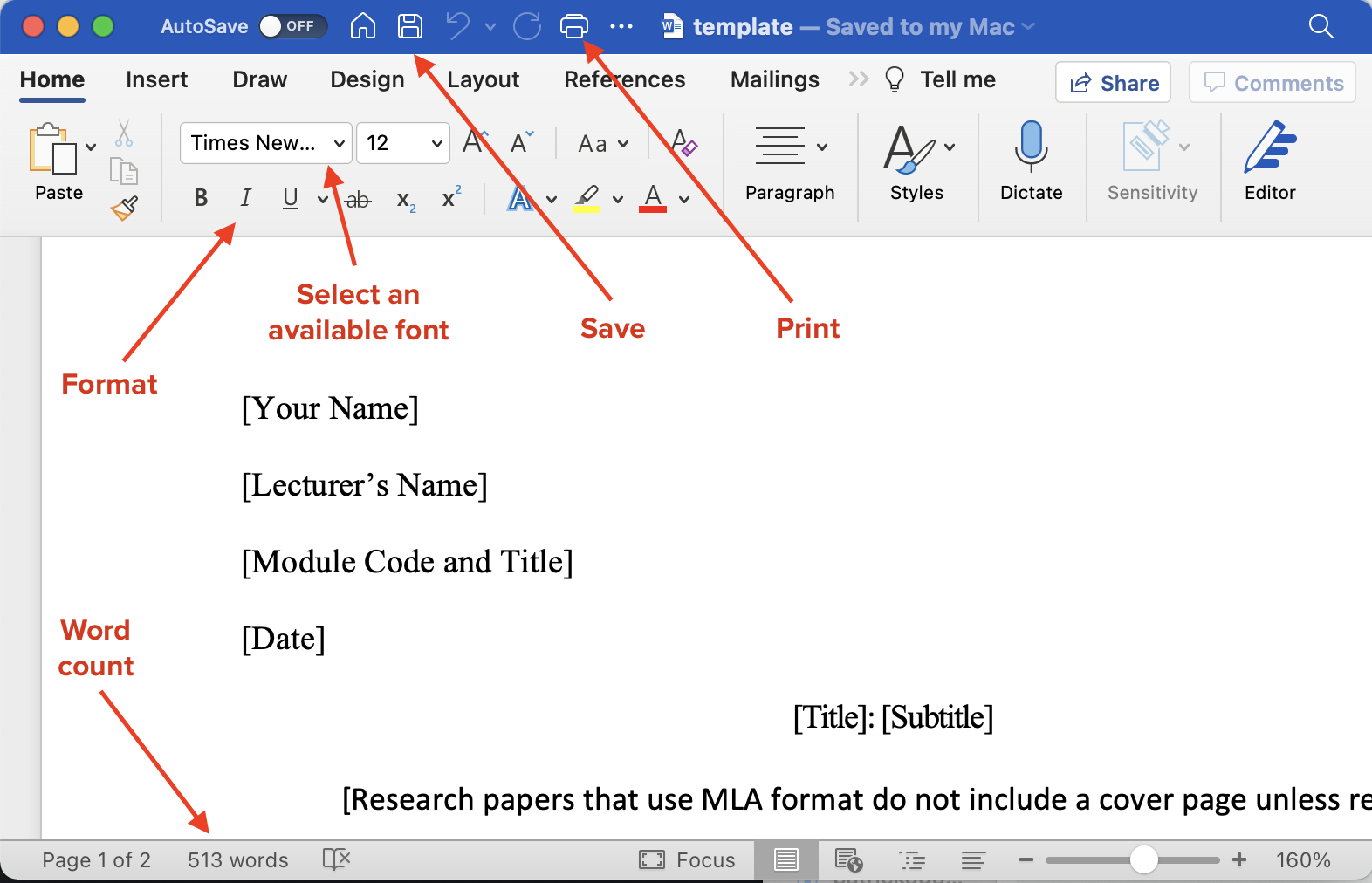

A word-processing file: data and operations

So, to take another example, a word-processing file contains data in the form of content and a computer application allows you to perform various operations on it. You can save the content as a file, in other words, store all of the data on your hard disk — or on a remote server “in the cloud”. You can print the file if you have a printer attached as a peripheral, or by sending data over the internet to a connected printer. Word-processing applications make use of a graphical interface, which means that you can click on an icon to select bold or italic fonts, for example. Given that much of your work will consist of writing essays, you have everything to gain from becoming proficient in the use of these tools. And of course computers are fully equipped to carry out numerical calculations, like counting the number of words in a file or document.

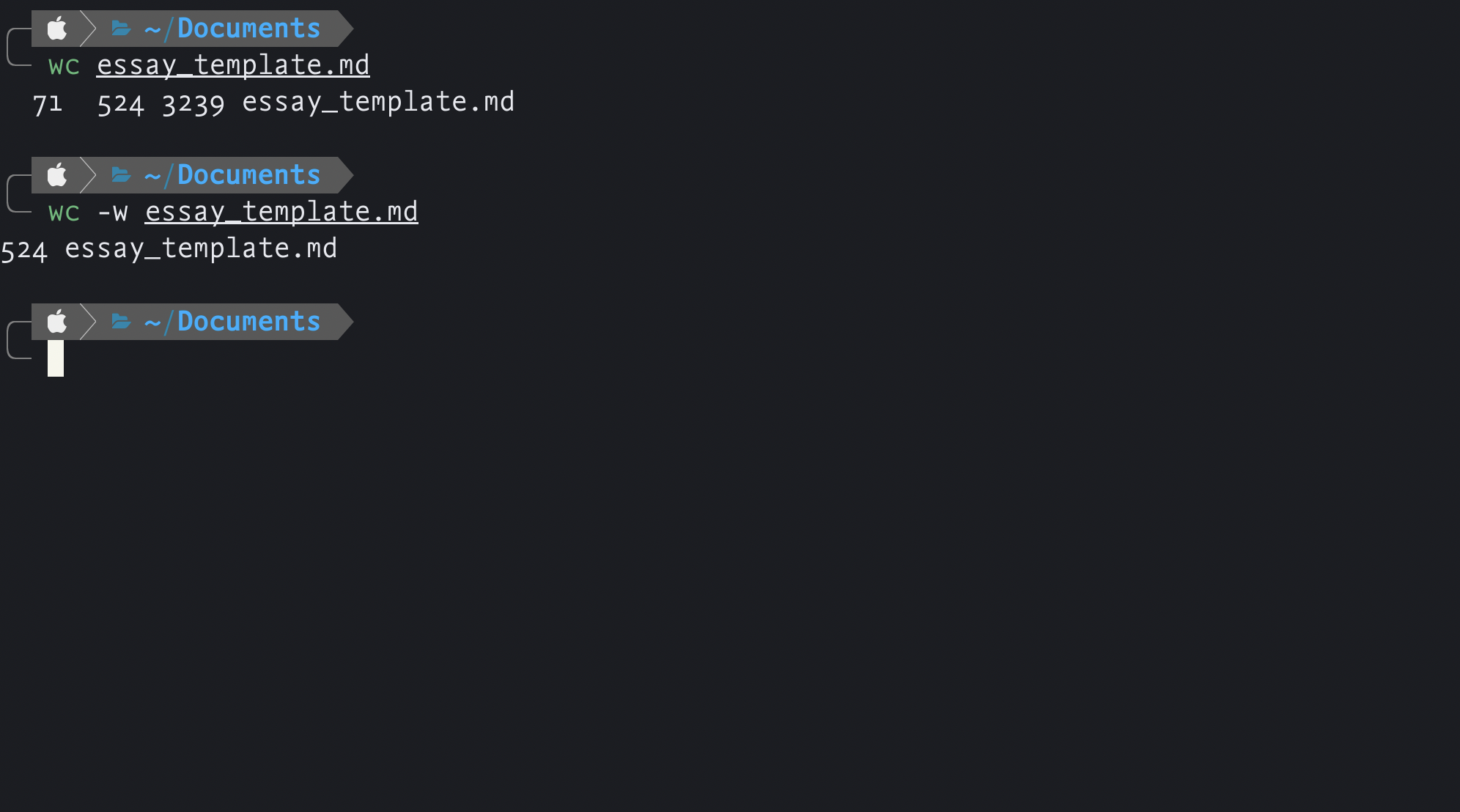

Word count using the command line

In its earlier realizations, a computer operated on the basis of typed instructions via the command line, rather than through a graphical interface. Here, a simple program is invoked using the command wc, or “word count”, and applied to data in the form of a markdown file. By default, the program counts the lines and characters, as well as the number of words, though you can also limit it to a word count only.

This is perhaps the simplest operation that you can carry out working on text using a computer. A computer will also help to you sort all of the words contained in a text in alphabetical order. It can also be used to retrieve lemmas, or to give the dictionary form of each word extracted from a text, e.g. ‘to do’ from ‘done’. It can count and display occurrences of individual words, or tokens, in a given text.

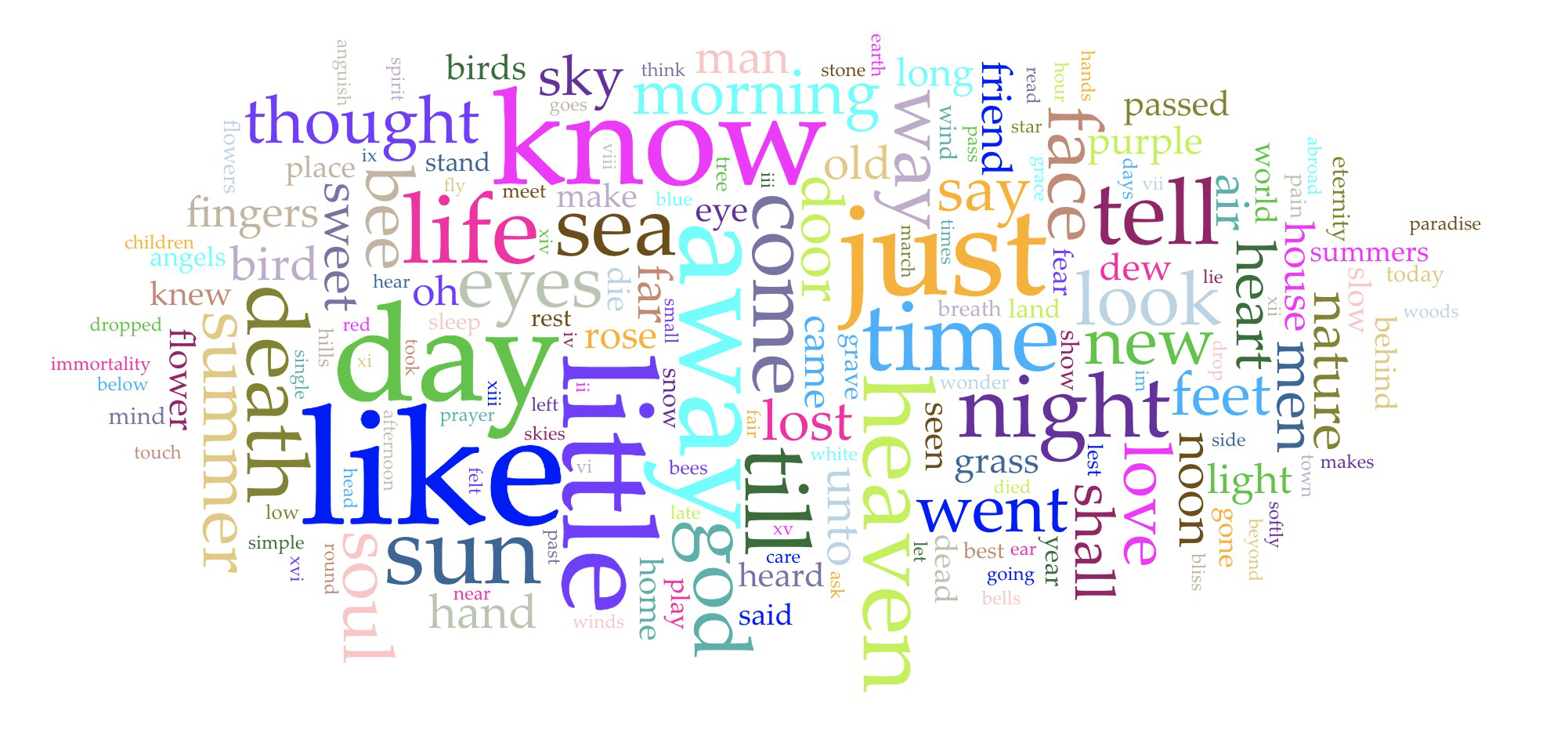

Word tokens in a word cloud (source: Voyant Tools)

A web application like Voyant Tools can perform all of these operations, providing, as here, a word cloud displaying word-frequencies in the poems of Emily Dickinson.

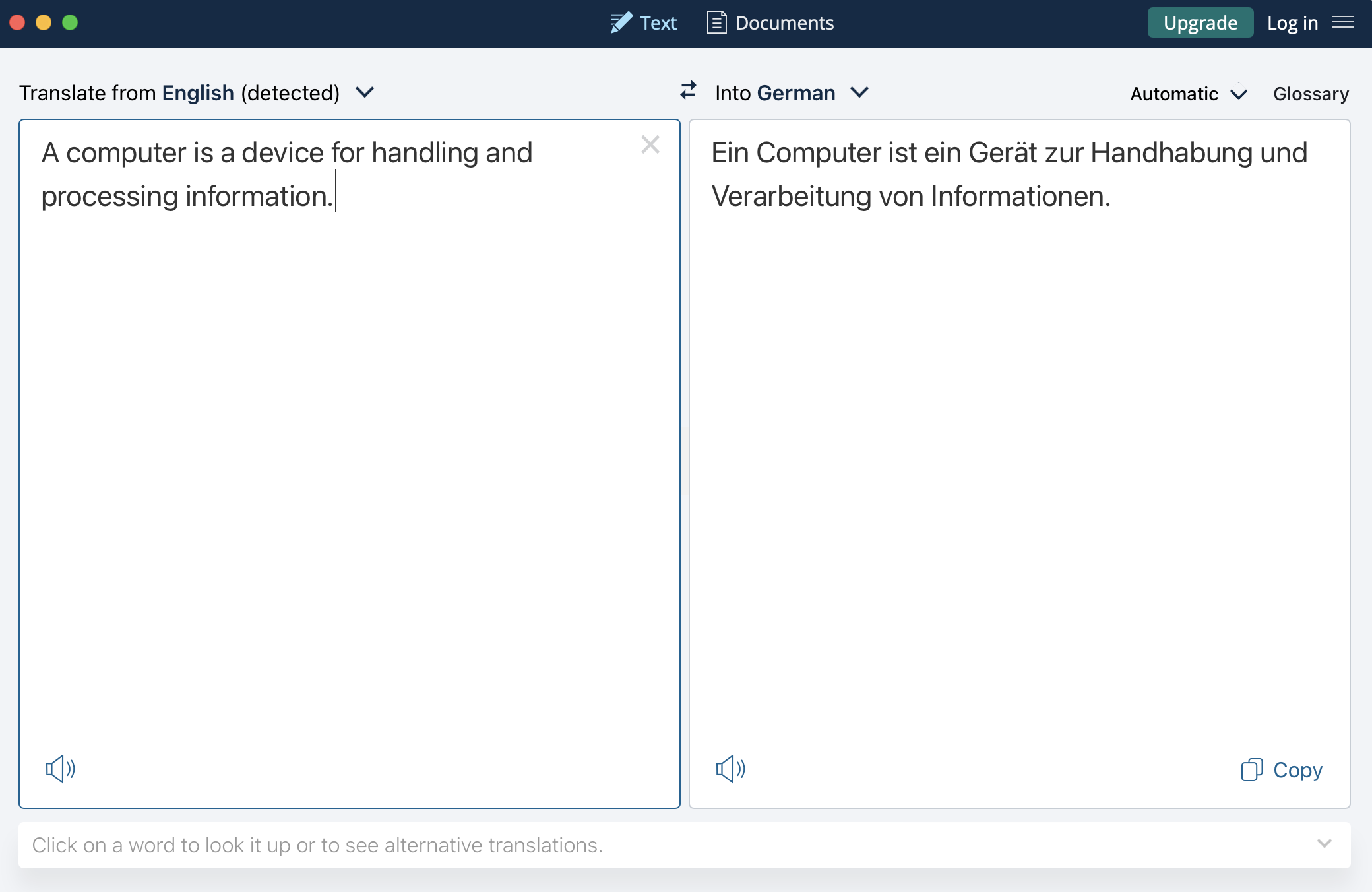

The computer as a device for transforming information

Today, we think of computers and similar devices as tools for studying how we can handle and transform information. In other words, the handling and processing of information are as signifcant as the devices themselves through which we study them.

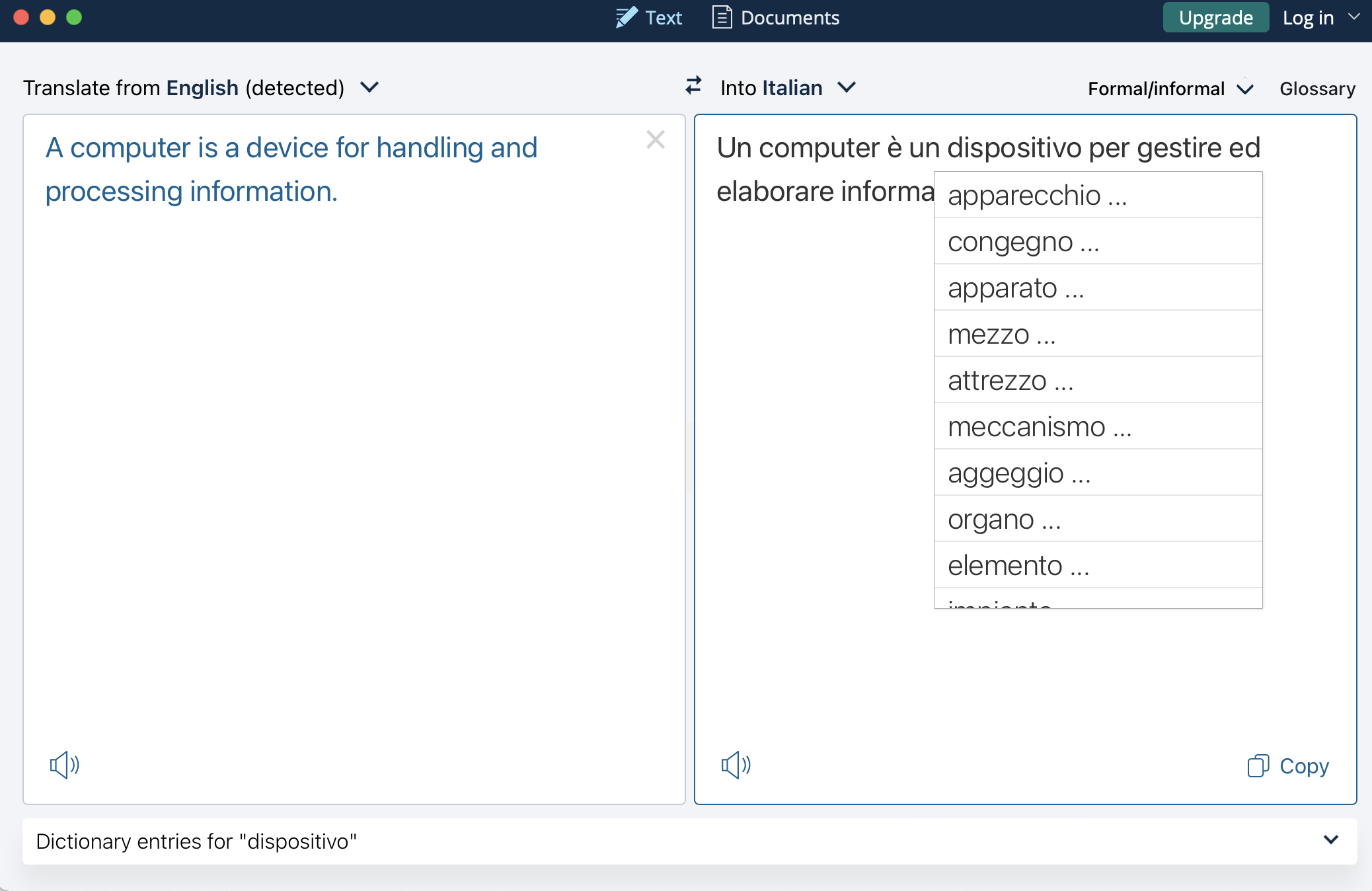

Processing information: the case of translation (source: DeepL)

A major area of development in information sciences is natural language processing and in turn automated translation. Here, a translation device operates on the basis of determining the likely probability of a sequence of words in one language being a suitable rendering of a given sequence in another — something that the computer application in equipped to do by drawing on a large volume of relevant linguistic data.

So, a computer can be thought of as a layered interactive device: you interact with it by entering a query and then the application in question interacts with the large volume of data available to it in order to provide a response.

Automated translation: alternatives for ‘dispositivo’ in the database

Computer operations

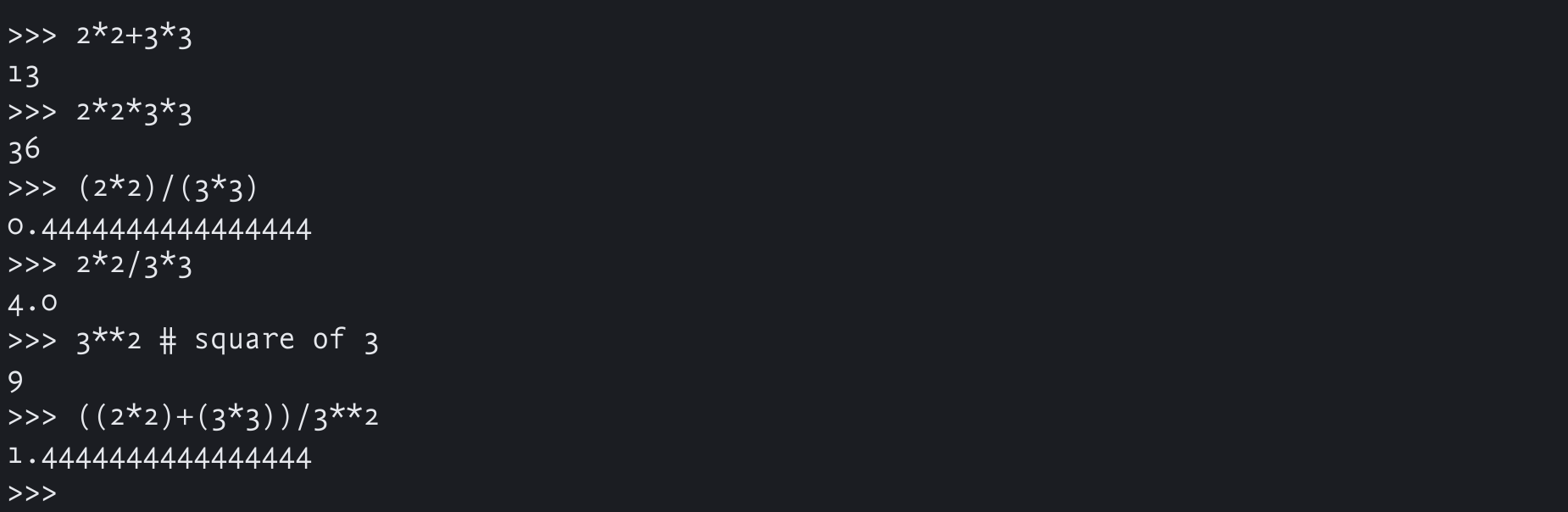

Originally, computers, as the term implies, were designed to handle computations.

Using a computer to calculate

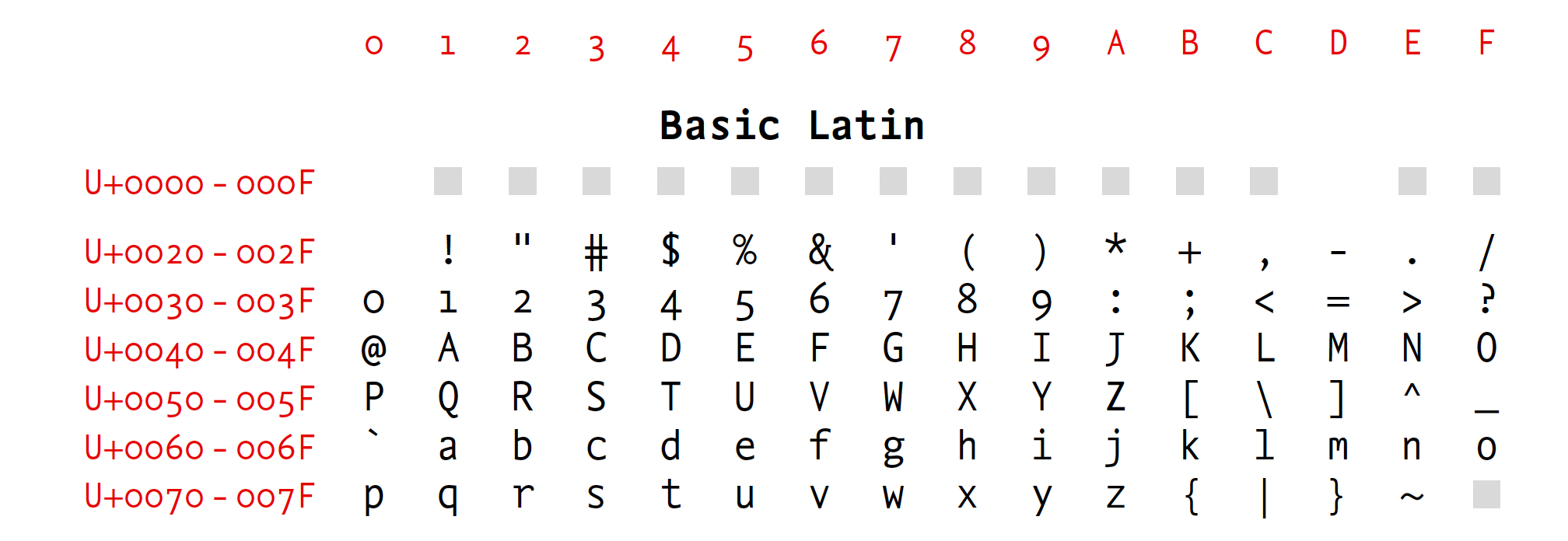

Needless to say, computers continue to be used in this way. Moreover, computers use numbers to store and handle data — for instance, the characters that make up a written script as displayed on a computer screen are encoded using numbers, specifically hexadecimal notation with a base of 16, that is, 0 to 9 and A to F.

Latin Script encoded using hexadecimal numbers

The upper case A character has a Unicode value of U+0041.

Now, as we have just seen, we think of computers also as devices to store and transform data, whether locally (on a disk) or remotely (in “the cloud”). A computer contains dedicated programs, or applications, which allow you, say, to create documents (whether word-processed files or PDFs), for instance, or to analyse large collections of data, using, for instance, applications like concordance tools.

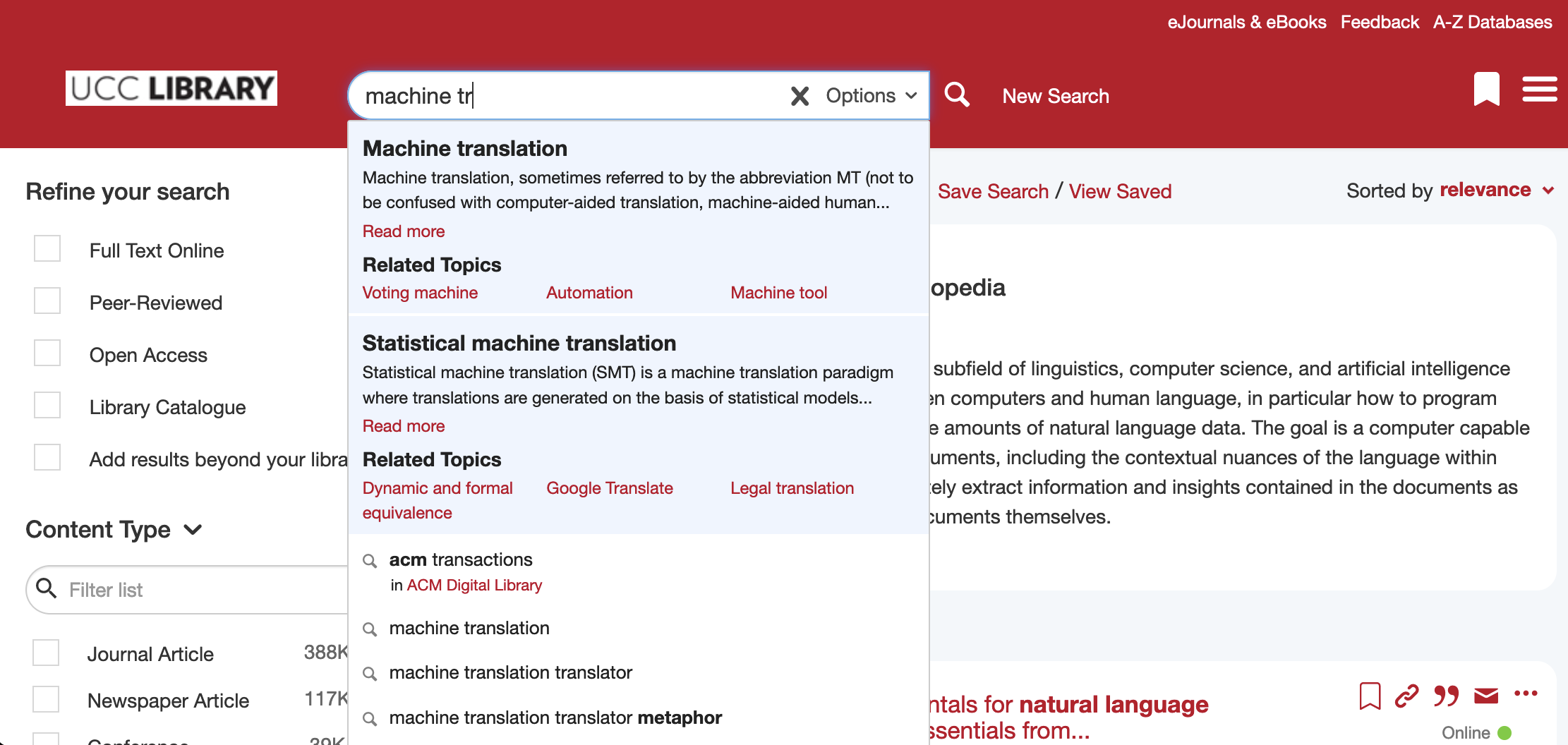

More and more, dedicated computer applications can help you in your research, e.g. by using web browsers to search the internet or to access specialized collections of data held in a library.

Searching for information: aided by artificial intelligence

There is an active dimension to this process: when you begin to enter text, the web application itself mobilizes relevant information in order to anticipate the completion of your query. This is an instance of artificial intelligence in use: the search interface in question can draw on the very large amount of data generated by previous searches to predict with a higher degree of probability the exact scope of your search.

On the other hand, when you write an essay using a word-processor, you are creating data of your own, as well as accessing data from other sources that you may require, using search strategies like these. When you make reference to the sources that you find, you in turn can include links to remote online locations where they can in turn be accessed by your readers.

In other words, your work can trigger further interactions with information on the part of others using computers.

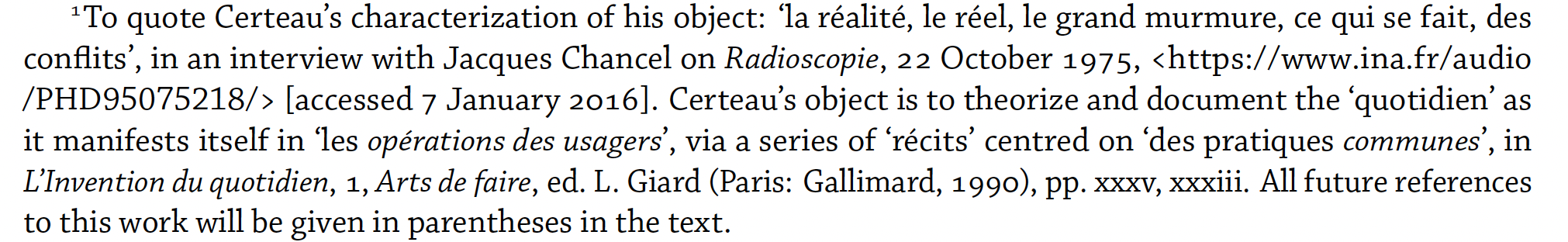

A reference with a hyperlink to an online source

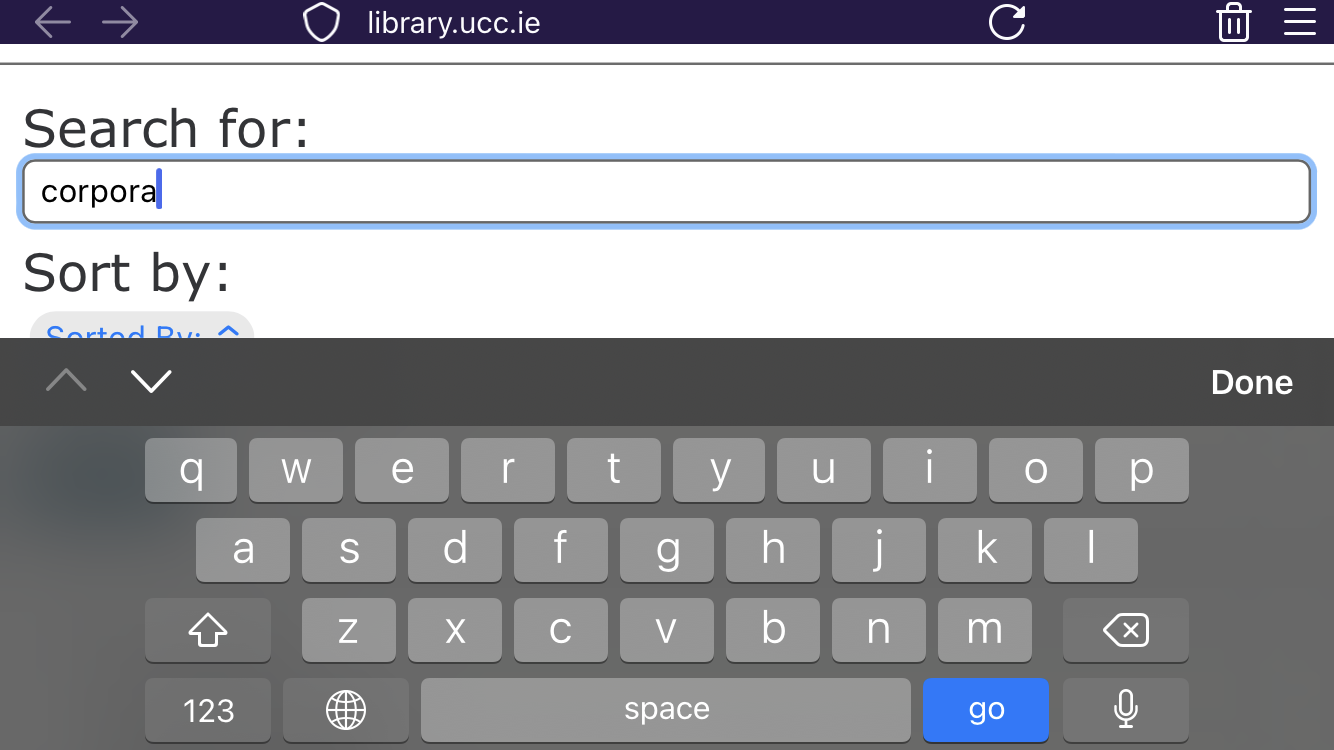

A traditional computer allows you to carry out these interactions via peripherals, like a keyboard. But today you can use a smartphone as a computer, in which case you carry out operations with it via a virtual keyboard.

Using a smartphone to search a library catalogue via the web

The computer as archive

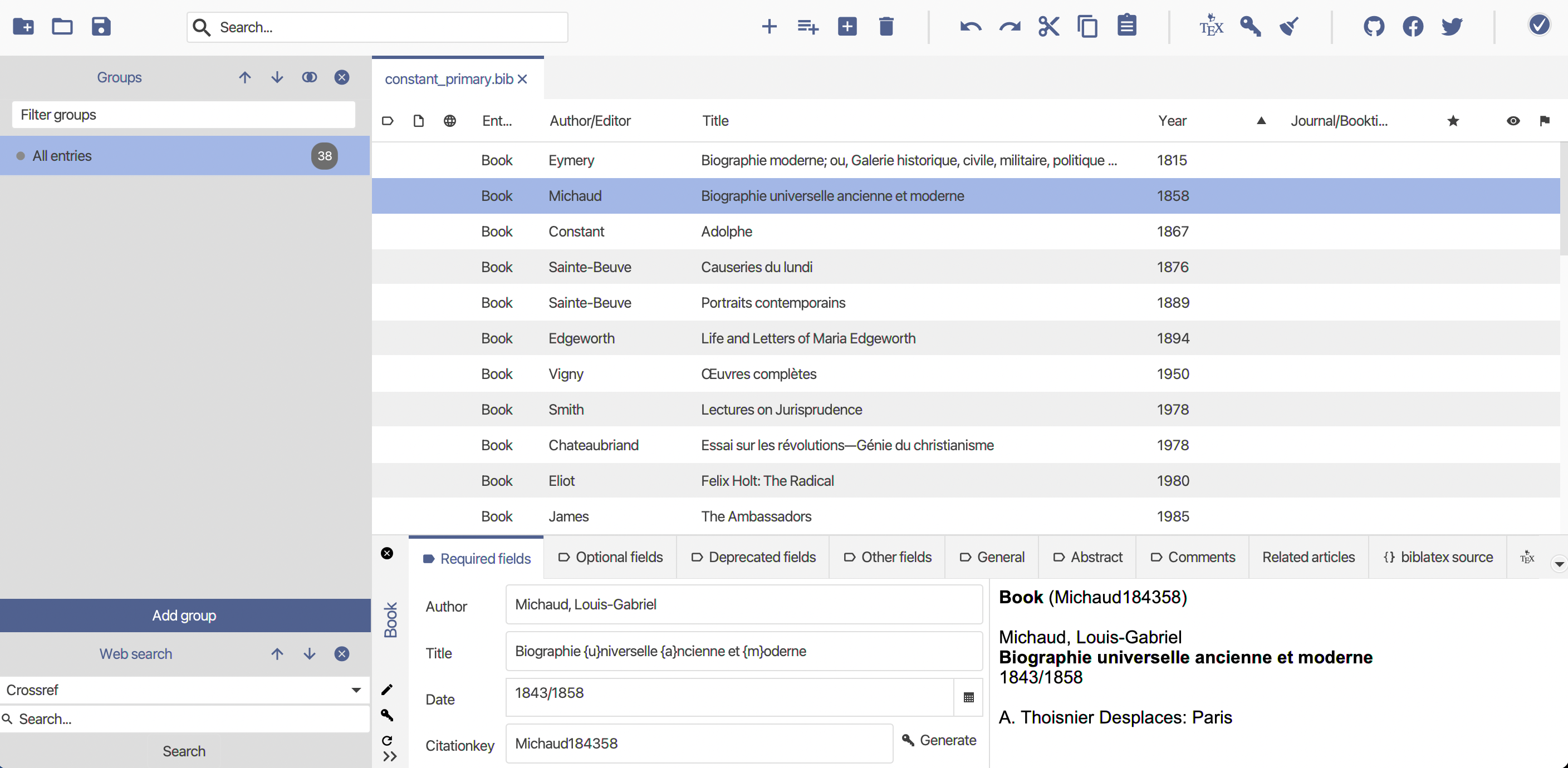

At the same time, a computer can be understood as an archive or database, containing information and data that you yourself may have assembled. These data can be materials that you create, like your notes or essays, or collections of materials relevant to your work, which you can catalogue and organize using further dedicated applications.

Using Jabref as a bibliographical archive

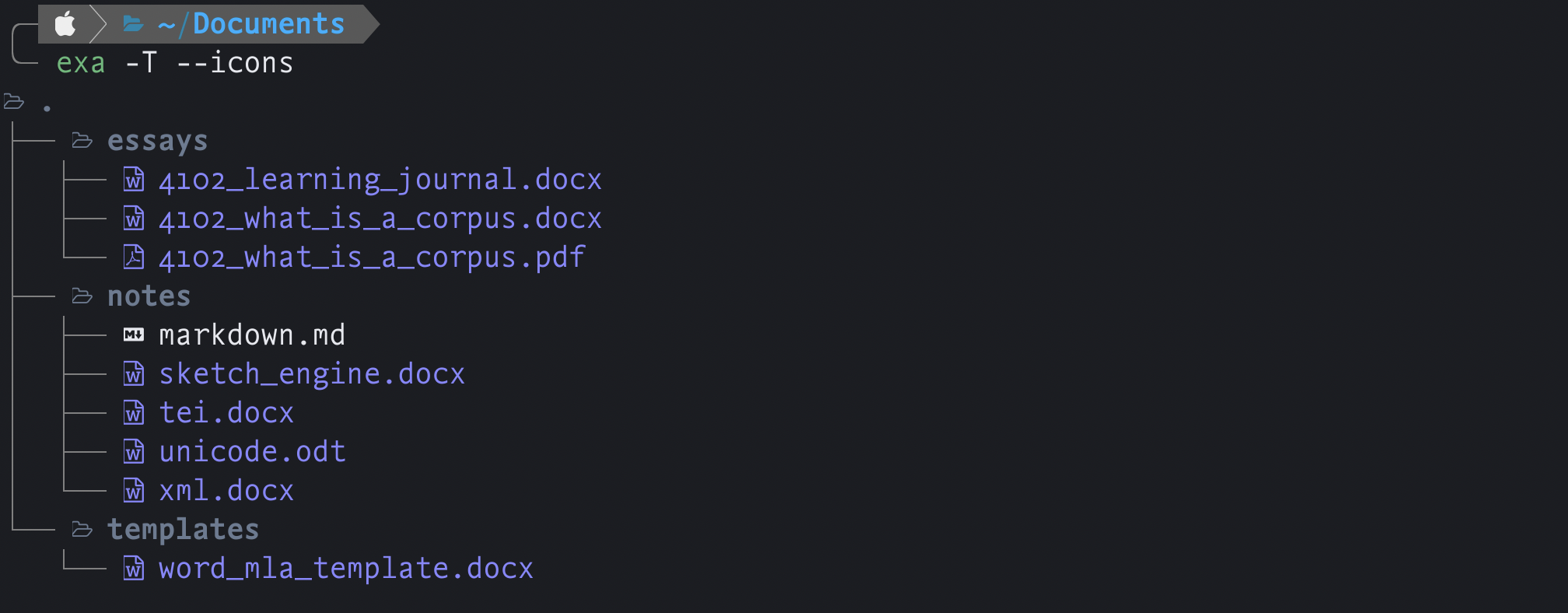

It’s a good idea to aim to be organized in how you store information on your own devices, making effective use of the hierarchical structure of computer file management.

The hierarchical directory system: the Documents folder in macOS

For instance, you could create a directory for each of your courses, with sub-directories where relevant to organize your material. Local directories on your own machine or remote ones in the cloud all have the same structure and so can be organized in the same way.

Tip

It’s a very good idea to have backups of all of your files and data, by using, for instance, one of the cloud services provided by the University.Computers have now also become much better equipped to carry out searches among your files and folders. In other words, you don’t always have to explore the entire tree structure of all of your directories to retrieve an item.

How to search: activating Spotlight in macOS

In macOS, a single interface can combine a wide range of searches.

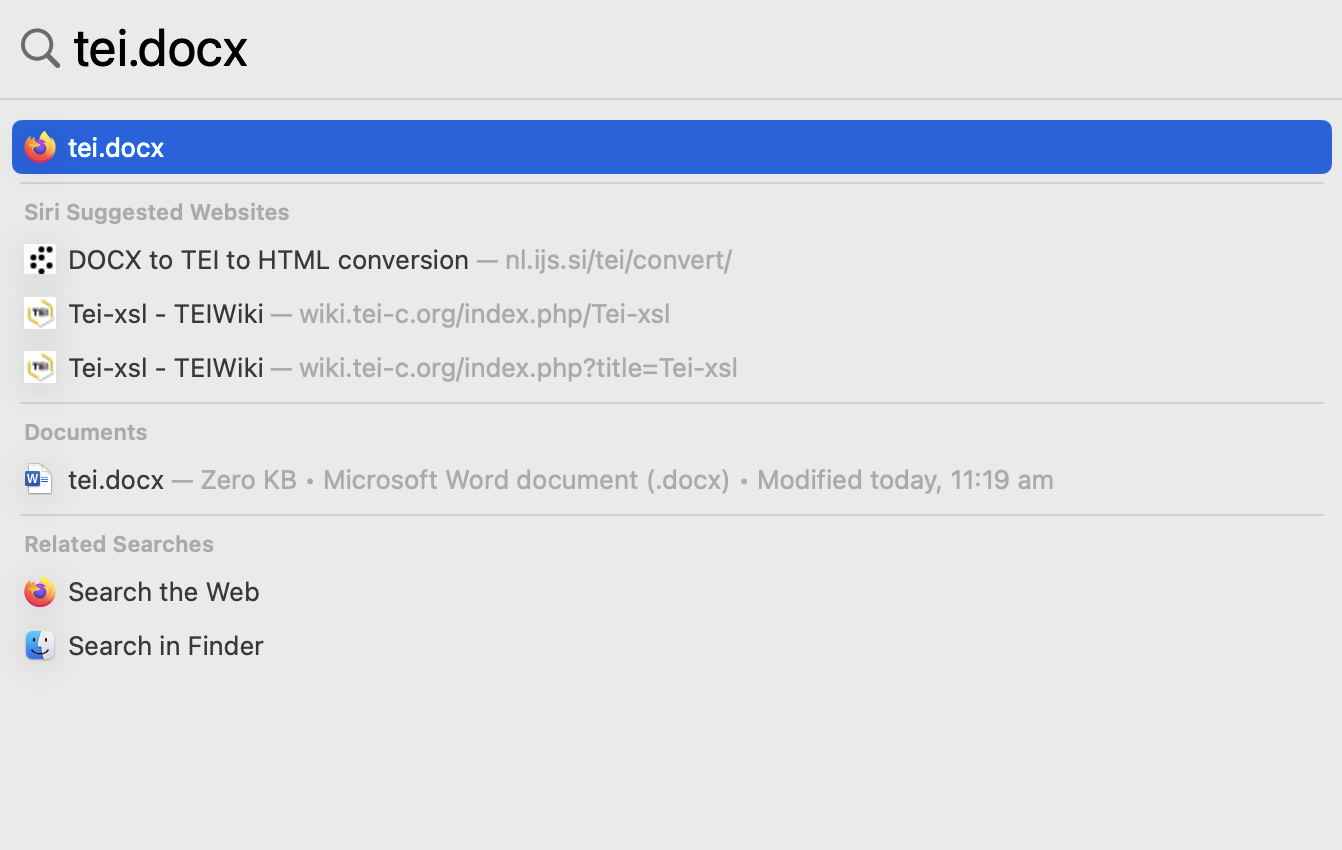

The results of a search: local and remote

The results in turn provide you not only with information on the contents of your files, but also point you in the direction of relevant internet sources.

How does a computer operate?

An operating system (or OS) is a system software that allows applications to interact with the computer’s hardware, for example, by allocating the computer’s resources and memory to the different applications that a user may invoke. The operating system also controls the device’s display and it functions independently of you as user, mobilizing the different components of the machine in response to your commands.

Operating systems are pervasive nowadays, extending to computers (e.g. Windows, macOS), smartphones (Android, iOS) and indeed televisions (tvOS, WebOS, AndroidTV).

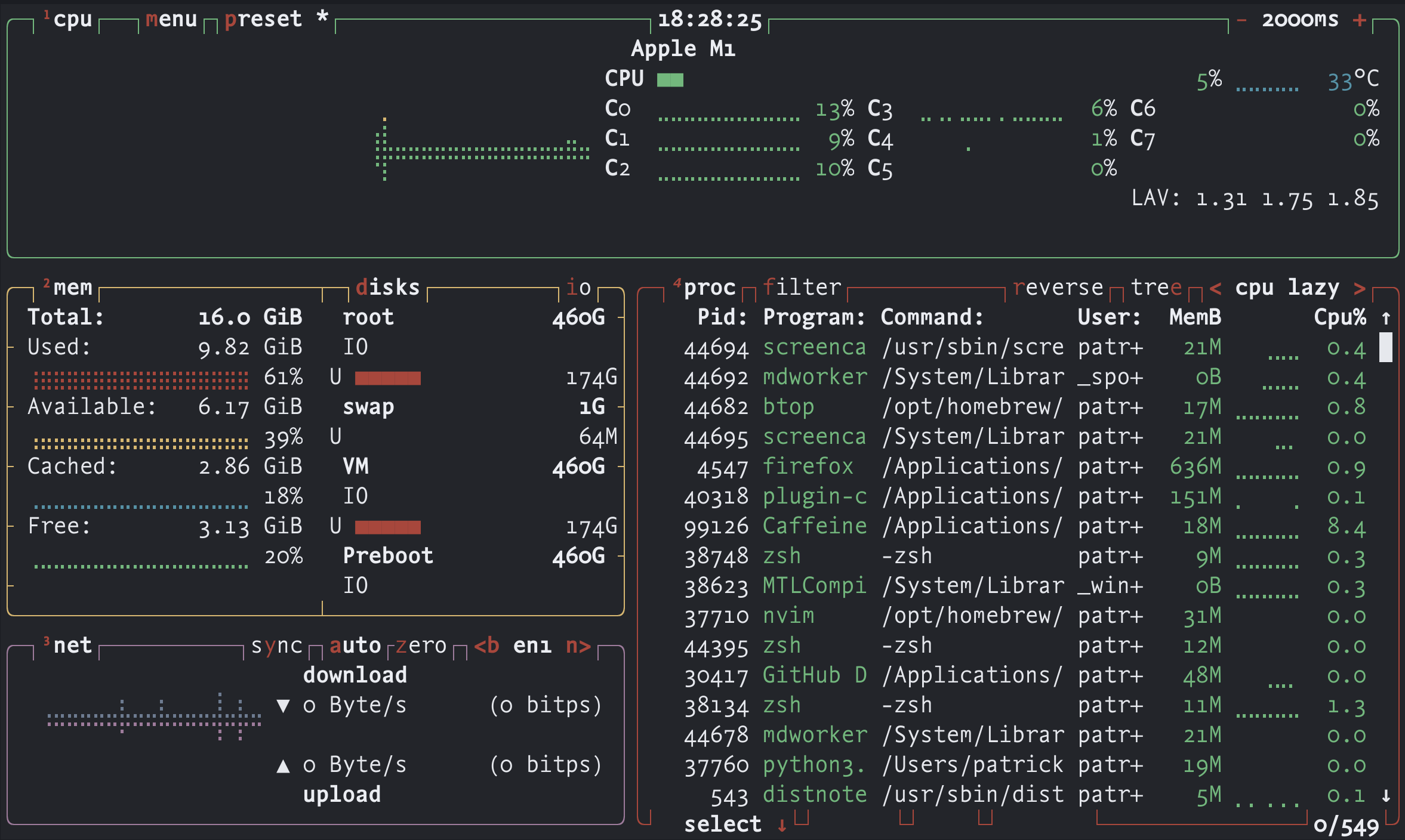

The operating system at work: the case of a computer

Any computer runs a number of software processes via the central processing unit, or CPU, at any one time. The CPU is thus a key component of the computer’s hardware. A computer uses its system memory, or RAM, in order to function, e.g. to make data available to the programs or applications that you may install on your machine while these are in use. A web browser (in this case, Firefox) typically makes heavy demands of this system of primary memory. A computer uses a different, more permanent, form of memory to store information on disks. And finally, most computers today have open net connections that allow you to access remote data via the internet and the World Wide Web. The operating system controls all of these processes and their interactions.

Tip

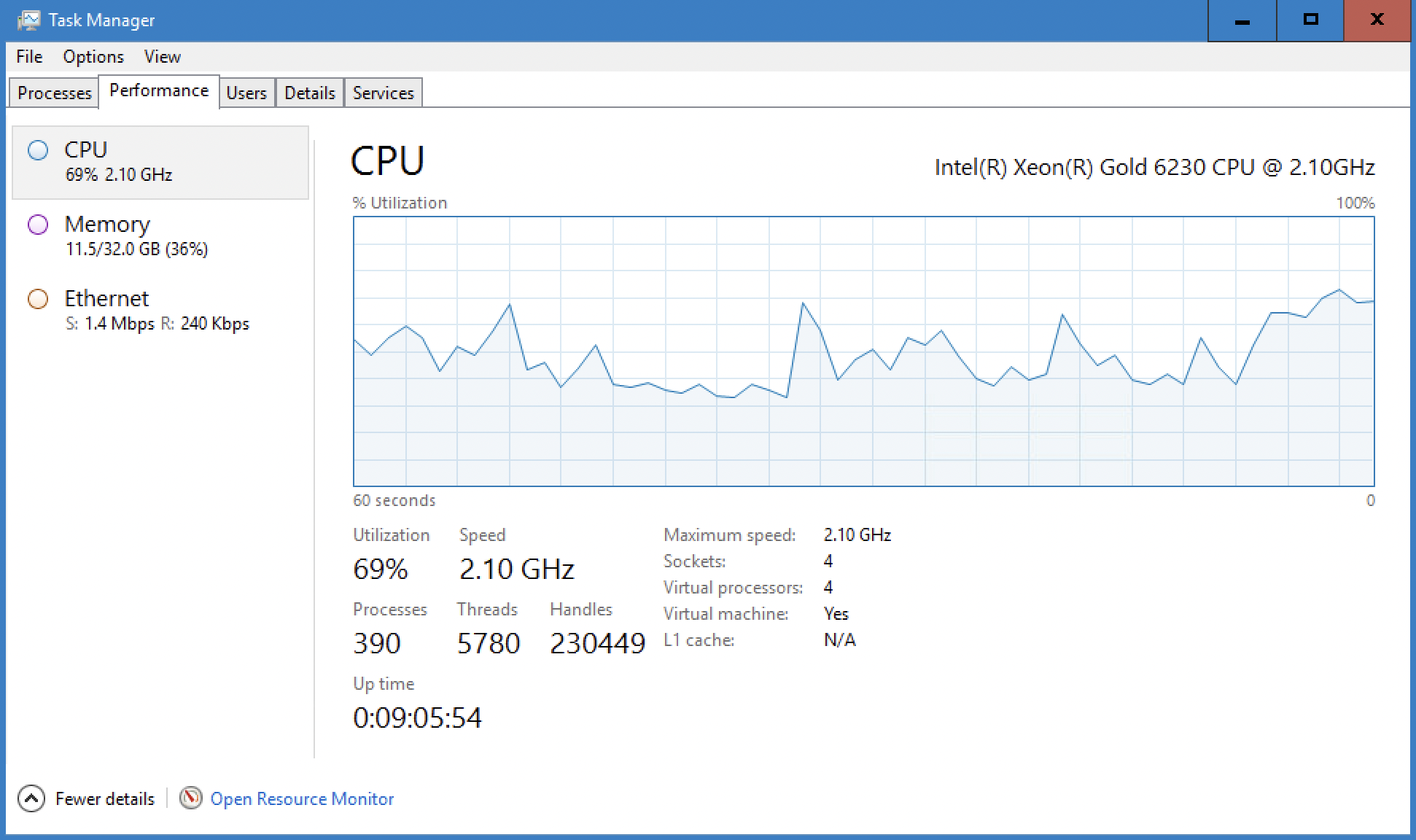

You can monitor just how your computer is functioning for yourself by using built-in applications like Task Manager in Windows or Activity Monitor in macOS.

System monitoring: Task Manager in Windows

Today, computers can be complex machines designed to fulfil a wide range of uses. Operating systems are designed to facilitate your interactions with a device, and with all of the information and processes on which you may draw in your work. For this reason, it makes sense to explore and learn just how Windows or macOS or Chrome OS operates and how each one can help you in your use of the different computers you are likely to encounter.

Text and hypertext: networks and the web

The web forms part of the internet, or the network of all connected networks. When you go online, for example via WiFi, you connect to a local area network. This network is in turn connected to innumerable other networks via specialized gateways and servers.

A webpage is located in a web domain, in other words a computer or group of computers that form a local area network of their own, and are likewise connected through a web server to the Internet. To connect to such a page, you activate, as you well know, a hyperlink which contains the web address of the domain and page in question.

Activating a hyperlink

Hyperlinks are thus the building blocks of the web. Here, you can see that the user has activated a given link by hovering over it with a mouse and that the hyperlink itself then appears in the bottom left-hand corner of the web browser (in this case, Firefox).

Your web browser will then retrieve and display the page. All of this information travels over the internet in the form of packets, using dedicated internet protocols for communication and exchange.

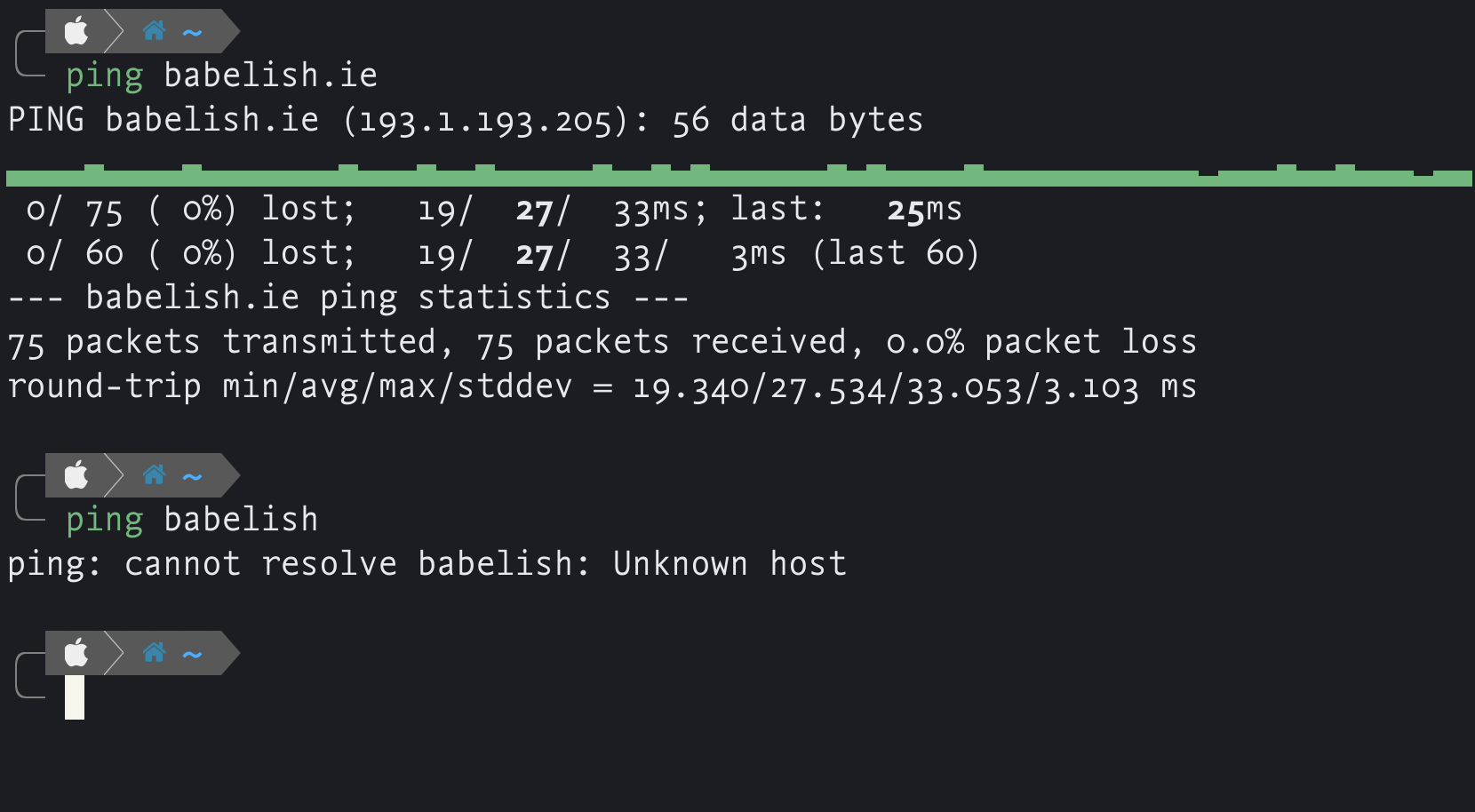

Checking a connection to a domain with the ‘ping’ command

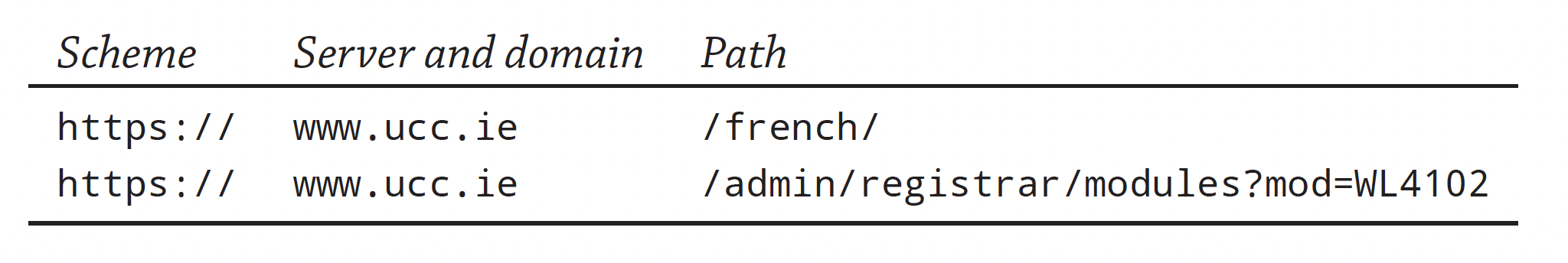

Web links are just one kind of uniform resource locator. They contain information about the domain where the resource to be retrieved is located (in the case below, www.ucc.ie) and, if necessary, the path to an individual item within the hierarchical directory structure.

Anatomy of a uniform resource locator: the case of a web link

You can also use the browser to send a command to the remote machine, in the second example, to search for and display information about a module with the code WL4102.

The internet has greatly modified our practice of reading and working with documents. It allows us to locate, document and retrieve sources of information, and in turn to embed connections to such sources in our own documents. These and other kinds of link can substantially expand the scope of your learning.